Feb 26, 2020 Managing Cats for Cats, Wildlife & People

In the January 2020 issue of our Tales of WellBeing, we related the story of an outdoor cat project on Key Largo, Florida, called ORCAT – Ocean Reef Cat Project. To most people the cat management project has been a big success, reducing the number of roaming outdoor cats from 1,900 or more at the end of the 20th century to around 200 within 20 years. However, US government staff with the Fish and Wildlife Service on Key Largo remain concerned about the roaming outdoor cats in the Ocean Reef community despite having trapped only a few of the ORCAT (micro-chipped) felines in the protected sanctuary in the past couple of years. In North America, Australia and New Zealand, suspicion and outright hostility continue to plague the debate over what to do about outdoor stray cats and truly feral cats, which exist with no human support whatsoever. By contrast the United Kingdom’s Royal Society for the Protection of Birds has stated that they do not perceive outdoor cats to be a threat to native birds.

Google Earth Pro, Imagery 2020 Lansat/Copernicus, Maxar Technologies, U.S Geological Survey, Map data 2020, Untied States, Key Largo,Fl, 25.219521,-80.323543

The RSPB acknowledges that outdoor cats kill birds in the UK, but they view such predation as “compensatory” rather than “additive” (i.e. cats prey on birds that would have been killed by other predators). Growing suspicion and hostility between cat advocates and wildlife biologists are hampering programs to reduce the impact of outdoor domestic cats on wildlife.

One of the major elements driving conflict between cat advocates and wildlife biologists is the practice of trapping outdoor stray and feral cats, sterilizing them, and then returning them to the site where they were trapped, a tactic known as Trap, Neuter, Return (TNR). Wildlife biologists argue that the sterilized cats continue to prey on wildlife after being returned (which everybody acknowledges) and that this practice does not “work,” a claim with which cat advocates strongly disagree.

Cat advocates argue that TNR, when implemented properly and with sufficient intensity over time, leads to a reduction in the number of outdoor cats and may even eliminate the outdoor cat population entirely, although the possibility of recruitment from the pet cat population is always an issue. Wildlife biologists argue that TNR does not meaningfully reduce outdoor cat populations and that the few cases of recorded reductions in the number of outdoor cats are mostly the result of adopting out trapped, socialized cats and not due to the impact of sterilization. This criticism, for example, was directed at a project undertaken on the University of Central Florida (UCF) campus in Orlando by Dr. Julie Levy and her team from the University of Florida in Gainesville. The initial 2003 report on the project noted that, of the 155 cats on the campus in 1991, all but one was sterilized by 1995. Seventy-three were removed for adoption, 14 were euthanized for health reasons and 68 were returned to the campus. By 2002, there were 22 cats remaining. In a recent re-examination of the project, Dan Spehar and Peter Wolf (2019) note that a total of 204 cats had been trapped on the UCF campus from 1991 to 2019 (another 49 over the original 155 first found on the campus) and there were 10 cats remaining as of 2019.

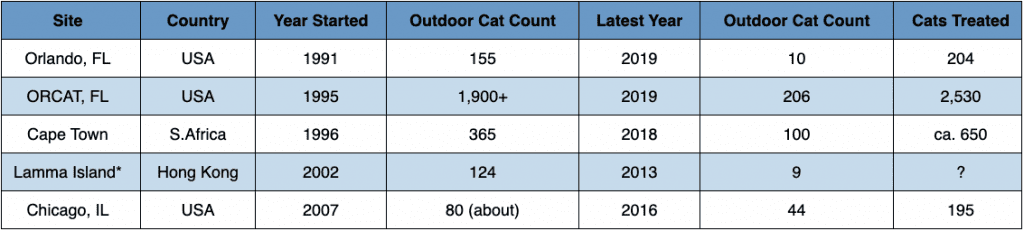

The table below identifies several TNR projects that have reported a reduction in the number of outdoor cats. Not all of these have been published in the academic literature, but they are included here to demonstrate that a reduction in outdoor cat numbers is possible even if the total count is not reduced to zero. For example, of the 2,530 cats handled in the ORCAT project since 1995, 1,419 were removed (510 adopted, 58 died in care, 441 were euthanized for health reasons, 210 were picked up dead and 201 were being housed in the adoption center) and 1,111 were returned to the site at which they were trapped. There were 1,691 sterilizations performed from 1995 through 2017 and 206 outdoor cats now remain.

* Cat count on an index route – not a complete count of cats on the island.

There are other reports of successful TNR projects that “work,” but the above examples provide something of a blueprint for what is needed. Ideally, the projects need to be sustained for long periods (at least 10 years) and must be monitored relatively closely.

The availability of time and financial resources to address outdoor cat issues are other elements that should be taken into consideration when considering what to do about outdoor cats. In the USA, there are considerable resources available to implement TNR projects. Animal protection groups have access to almost $5 billion per year to address animal issues. In addition, around 10% of US households feed outdoor cats they do not own and many of these households will volunteer to assist with TNR projects. In contrast, proponents of trapping and killing cats have almost no resources and have had very limited success in stopping TNR projects in the USA.

Instead, it would be much more constructive for wildlife and cat advocates to team up to address the outdoor cat issue. Such co-operation is currently very rare but the partnership between Portland Audubon and the Feral Cat Coalition, also of Portland, is a model that should be followed globally. Both groups bring resources and complementary skills to the project instead of using their resources to support unproductive conflict. While we wait for progress reports on their joint project, it is pertinent to note that cat intake into the Portland Alliance shelters from local communities has dropped from 23,000 in 2006/7 to 10,000 in 2018. Similarly, the DC Cat Count is a project that has brought animal protection groups and conservation biologists together to develop a comprehensive picture of domestic cat populations in a defined community and the number of outdoor cats in that community.