Aug 17, 2023 The Asian Elephant: Training and Control (Part 2)

The Thai Government has a long tradition of managing elephants. Thai laws regulating the treatment of elephants have been adapted to address elephants involved in the tourist industry. If one only seeks improved conditions for the elephants in the service of man, it is the implementation of the laws rather than the law itself that should be challenged.

Some advocates do not want elephants employed in the tourist industry and have focused their protests on a critical activity, arguing that elephants should not be used to provide tourist rides. However, elephants have been used to transport people for thousands of years, and Thai regulations allow the elephant to carry up to a maximum of 10% of the elephant’s weight (3000-5000kg). By comparison, the normal maximum load for the saddle and rider on a horse is 20% of the horse’s weight.

The pressure from the West against the riding of elephants has shifted tourists to watching elephants in large enclosures or to tourists feeding the elephants. With demands for a “no chain – no hook” policy, it may be possible to employ mostly female elephants. However, the more aggressive females and most males would be chained and kept out of sight of the tourists. Elephant owners depend on income from tourists or donations from big animal organizations. But some elephant owners are shifting to sponsorships of individual elephants by Facebook followers. These sponsorship sites are updated daily via videos from the mahout (the elephant carer and trainer) showing almost everything the elephant does.

It is generally accepted that humans need to control domestic animals to benefit both people and animals. Control is especially important in the case of the elephant. It is the only animal in the service of man that is so big and strong that it cannot be controlled simply by force. A successful relationship between humans and elephants requires mutual respect. When the training of elephants was first developed, the process depended on wild-caught elephants. Because it was difficult to raise a baby elephant away from the mother, the traditional training starts when the baby is 3-5 years old. In Thailand, the law stipulates that the baby must be more than 30 months old before being taken from its mother for training.

A Myanmar example shows a traditional training situation.

Traditional training starts with a Buddhist ceremony. Then the young elephant is tied up, and the mother is removed. There are still bonds between the baby and its mother, and they protest the separation. The young elephant must then learn that it no longer has any control. It is tied up with soft ropes or placed in a cage so small that it cannot turn around. A group of mahouts keeps the elephant awake either by harassment or by singing to the baby all night. After three days of this confinement, the young elephants realize they are no longer in control and give up. They are then offered food, and the actual training can start. Older elephants often serve as “instructors” during training to calm the young. This method of breaking elephants has been developed over centuries and is very successful.

However, videos of traditional training methods were produced and were widely distributed. With good reason, the videos raised welfare concerns, and questions were asked if such training could be justified. Horses used to be broken by using dominance methods (“rough riding”) until the horse accepted the rider’s control. In the West, such “breaking” of horses is no longer accepted, and new, “gentle” training methods have been developed. The best approach so far for the gentle training of elephants was suggested and then developed by Australian horse trainers.

An example of gentle training | Photo credit: Bjarne Clausen

The principle is quite simple. It starts with the trainer standing in front of the young elephant, pressing on the forehead, and pushing the elephant back. When the elephant moves back, it receives a reward. Elephants like sweet fruits such as a tamarin and quickly focus on obtaining another reward. Very soon, no pushing is required, and the elephant moves back on a verbal command. One can also quickly get an elephant to lift its head by using a pointed object under the lower jaw or holding a banana above it.

Despite the success of these gentle training methods, it was unrealistic to switch approaches overnight after centuries of reliance on the more forceful training methods. But outside pressure and a worldwide growing understanding of animal welfare have led to the increased application of gentle training methods for elephants. Manuals about gentle training have been translated into the Thai and Burmese languages, and a smartphone app for gentle training has been created for mahouts. In addition, gentle training using rewards can be introduced when an elephant is only a few months old. In Thailand, the National Elephant Institute’s training of young elephants now involves limited confinement and no forced roping. The new methods produce elephants that are just as well trained as in the past.

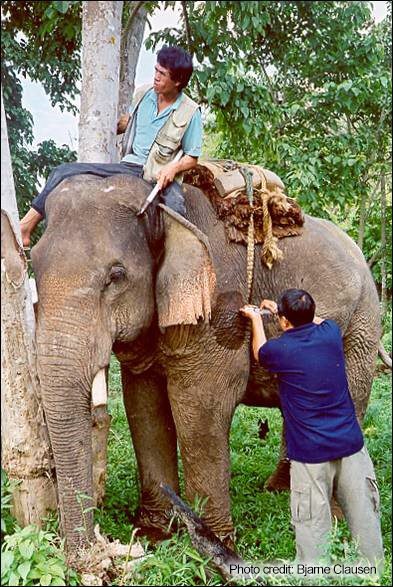

A veterinarian is treating an elephant while under the mahout’s control. | Photo credit: Bjarne Clausen

As mentioned in the introduction, one cannot work with animals, especially elephants, without training and reliable control. Elephants are potentially very dangerous animals. In zoos, where there is no mahout tradition, the standard for elephant care now usually permits only protected contact. However, the management of elephants in South East Asia is typically via free contact, similar to interacting with working horses in the West. Over centuries, tools for controlling animals have been developed. Often these tools inflict pain. Some tools – such as the ring in a bull’s nose – only work because of the pain. Modern ideas about animal welfare are forcing a reassessment of many pain-causing tools. Some of these tools remain, but their use has been restricted and regulated, such as the whip used in horse management. The main tool for controlling elephants in South Asia is the hook. Used correctly, that is, by simply touching the skin, the hook reminds the elephant that the mahout is in charge, and the veterinarian can safely treat the elephant.

The pointed hook also protects the mahout if the elephant becomes aggressive. The mahout uses the hook to avoid more serious conflicts. But the hook can be misused and injure the elephant. The solution is not to remove the only tool the mahout has for protection, but education, education, and more education. The regulations for Thai elephant camps emphasize the importance of mahout education. There are also several good educational books available in Thai for mahout education.

Elephants in the wild or in the service of humans have killed or injured people. But why? The adult elephant, nearly always the male, develops a hormone disturbance called musth, where the elephant can be unpredictable and very aggressive. Traditionally the owner deals with musth by tying the elephant to a tree with shade near permanent water. The elephant is then offered limited, low-protein food until the musth condition ends after several weeks. Accidents may occur because the mahout misses the early signs of musth, the elephant may break its chain, or some other unpredictable elephant behavior may lead to an accident. Again, the proper training of mahouts is essential. It is doubtful that selective breeding alone could eliminate the musth condition. Elephants not experiencing musth may also injure or kill people. However, so many different circumstances may be involved that this unfortunate behavior cannot be explained by pointing to a single cause. Most commonly, the victim of elephant aggression is the owner or mahout, who is involved in the daily management and care of the elephant. The successful control of an elephant depends on mutual respect between man and elephant, and anything that changes this mutual respect may lead to a dangerous incident. A mahout lives in a male-dominated world, often involving drinking. Alcohol may alter the relationship between the mahout and the elephant, or the mahout may be less careful and cause a dangerous situation. Some have asked if “rough training” may lead to a potentially dangerous elephant later. Nobody knows for sure, but it is one more reason for requiring more mahout training.

The new ideas of free elephant management and pressure from the West to ban chaining and the hook has yet to make the situation any easier for the mahout.

—————————————————————————————————————————–

Bjarne Clausen, DVM, is a veterinary consultant for Danish Animal Protection (Dyrenes Beskyttelse). Taweepoke Angkawanish, Ph.D. is head of Thai Elephant Conservation, National Elephant Institute. They have around fifty years of experience in Asian elephant welfare, care, and medicine.