Sep 30, 2024 “Gregory Berns’ Journey: Uncovering the Emotional Lives of Cows and Other Animals” by Joyce D’Silva and Carol McKenna

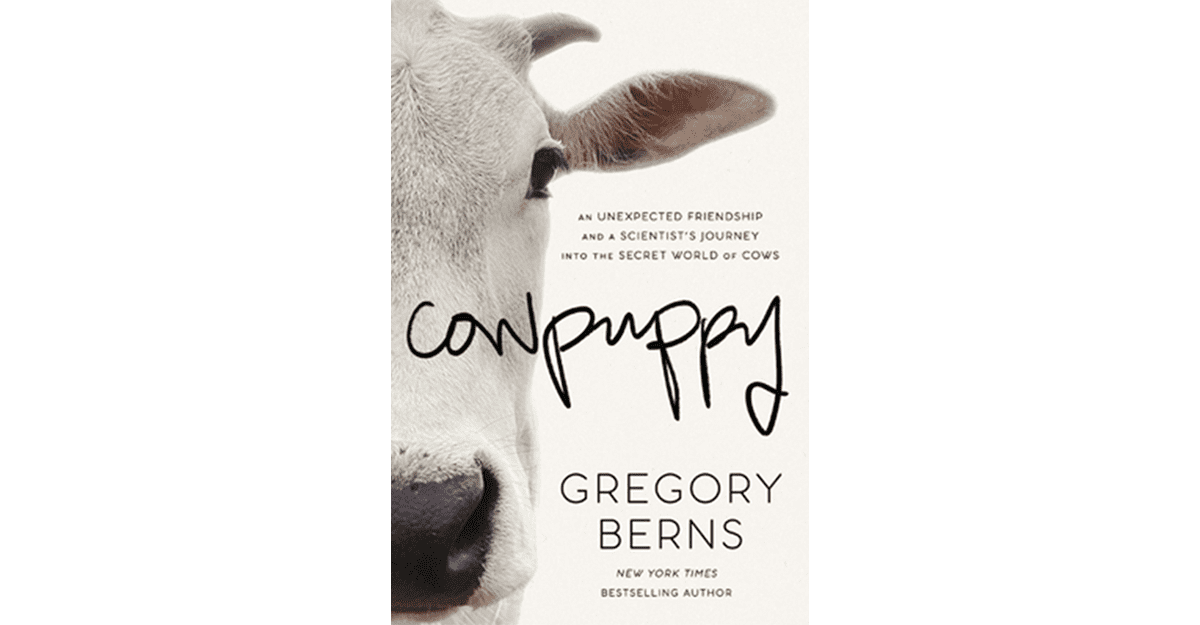

Book review of Cowpuppy by Gregory Berns, published by Harper Collins, 2024

As in the immortal film classic about the rescue of Elsa the baby lion, where the opening scenes cover the struggle to persuade the motherless cub Elsa to drink milk to survive, Gregory Berns also starts his adventures on a farm in Georgia with the desperate efforts to get a newborn calf to drink milk. (Spoiler alert: in both cases, they do drink the milk and thrive).

Thereafter, Bern’s book is a very readable, personal testament to a human discovering that other species are capable of traits too often assumed to be special only to humans: intelligence, love, other emotions, loyalty and social bonding.

The second calf, born a month later, is named BB and becomes the “cowpuppy” of the book title. Berns had acquired a herd of Zebu (small) cows as pasture managers. As Jane Goodall did in describing the individual personalities of wild chimpanzees, Berns learns and shares the individuality of each cow, the complexity of their social relations and names them. Berns comments that people rarely name cows and notes, “Nobody wants to think about the personality of the cow that has turned into a standing rib roast.”

A neuroscientist by training, Berns weaves together his personal journey from science lab to his career pivot to managing a farm with accessible scientific explanations of animal behavior and along the way explores themes about rural life, problem-solving, and community kindness. BB stood out due to his playful and affectionate nature, similar to that of a large puppy.

Previously, Berns specialized in studying dogs. His “Dog Project” involved training dogs to lie motionless in an MRI scanner, starting with his own dog, Callie so he could use the scanner to track brain activity in the dogs and study what the dogs might be thinking. His book “How Dogs Love Us” challenges traditional views of dogs by highlighting their emotional complexity. Berns’ research has shown that dogs are cognitively similar to a human toddler, suggesting that dog training methods should encourage problem-solving and independent thinking. This approach helps dogs learn faster and become more confident. Berns notes that cows have not benefited from neuroscience research because of the prevailing assumption that cows are dumb, but explains that cow brains are moderately large with a degree of folding (indicative of intelligence) comparable to primates. His follow-up book “What It’s Like to Be a Dog” extends the same themes to other species, including sea lions and dolphins. Berns describes the similarities between animal and human brains and argues for kinder treatment of animals.

When he bought the farm, he named it “Talking Dogs Farm.” On this 85-acre farm, surrounded by woodlands and wetlands and next to the Flint River, Berns embraced regenerative agricultural practices, including regenerative no-till farming and crop rotation (for soil health). The farm includes a vegetable garden and chickens, contributing to a self-sustaining ecosystem where each component supports the others. Berns goes to great lengths to detail how the rural community for miles around him was vital in helping him adapt to his new lifestyle and enabling him to survive as a farmer. Among his biggest wars were against mud and ticks. Geotextile fabric, bedding and drainage helped with the mud. Keeping grass short with the help of his bovine “pasture managers” reduced the tick problem.

Dogs have a longer history with humans, coevolving longer than domesticated cattle. The human experience with dogs eases the way for humans to identify with cows. Berns found that dogs and cows share many cognitive and emotional skills. Berns notes that the five dimensions of human personality also appear to fit other species, including cows. These dimensions include: 1. Aggressiveness, 2. Openness to experience, 3. Boldness, 4. Activity and 5. Extraversion. Young cows also enjoy locomotor play, shaking or running about, object play (with things), and social play, chasing and butting one another.

As Berns spent more time with his cows (the first three were named Lucy, Ethel and Ricky after I Love Lucy), Berns documents how cows possess impressive memories and are capable of forming lasting bonds with humans, much like dogs. As depicted for Sudanese refugees living in the US, seen in the movie “The Good Lie,” who find solace among cattle herds, Berns writes, “Whenever I felt the weight of life’s challenges, I sought out the cows. I often found myself drifting off into a meditative state after these sessions. I felt relaxed in a way that I hadn’t before.”

Chapters are dedicated to cow (moo) communications and cows’ recognition of themselves in the mirror he provided to see how they would respond [the Mirror Test is a classic technique to identify those animal species who view their mirror image as self rather than other]. The book concludes with descriptions of how his cows helped visiting strangers relax and allowed petting, similar to the use of dogs in prisons and hospitals. Berns’ book is a testament to the James Herriot quote he references: “if having a soul means being able to feel love and loyalty and gratitude, then animals are better off than a lot of humans.” (All Creatures Great and Small, page 87.)

Leslie Barcus is a member of WBI’s Board and the CEO of Nuzzles and Co, an animal shelter in Park City, Utah. Steven Hansch is a humanitarian aid specialist with extensive field, management, and evaluation experience. He teaches at several universities and serves on several nonprofit boards involved in human development and humanitarian aid.