Dec 17, 2025 COP30: Follow-up & Outcomes

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) meeting (COP30) was held in Belém, the capital of Pará in northern Brazil, from November 10 to 21, with an extra day added beyond the planned conclusion. While the meeting is usually identified as a COP (the 30th Conference of the Parties that signed the UNFCCC treaty), it was also CMP20 (the twentieth Conference of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol on climate change) and CMA 7 (the seventh Conference of the Parties to the Paris Agreement on climate change).

Significant political events, such as the Belém 2025 conference, generate fluctuations in terms of public attention intensity, individual and public processing of those events, and varying reports regarding the event. Perceived outcomes eventually stabilize, and a consensus emerges after a time on what was achieved and what failed to progress.

WellBeing International is following up on its COP30 article published the day before the official start of COP30 in Belém on November 10. That article focused on selected goals and objectives, including a discussion of the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), updates on the actual versus targeted temperature rise, and comments on scientific developments regarding climate change mitigation. A recap of the Belém conference details the complexities of global climate negotiations.

This article addresses time constraints to achieve projected goals, implementation challenges, the gap between funding aspirations and fiscal reality, and mechanisms that can effectively tackle climate change. The discussion will also consider the social and political disruptions that may accompany climate change and efforts to mitigate those disruptions.

UNFCCC and COP30: Goals and Objectives

The UNFCCC is the primary treaty that provides the vision and legal framework for how the world, its 190-plus nations, and regional communities can work together to stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations. The UNFCCC aims to prevent harmful human activities that adversely affect the environment while supporting sustainable development and allowing ecosystems the time and space to adapt to changing temperatures and protect global biodiversity. The annual climate COP (Conference of the Parties) is responsible for implementing the UNFCCC by setting milestones and developing the mechanisms required to achieve them.

A Core Mechanism – The Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs)

As of late 2025, 195 Parties (194 states and the European Union) had joined the Paris Agreement, representing nearly universal membership under the parent UNFCCC (signed by 198 Parties in total). [The USA is in the process of withdrawing from the Paris Agreement. That withdrawal does not officially take effect until January 27, 2026, after which the USA will join Iran, Libya and Yemen as the only countries that are not party to the Paris Agreement.]

Parties to the Paris Agreement are legally bound to prepare, communicate, and update their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) on a regular basis. Countries are required to update their NDCs every five years, report transparently on implementation through Biennial Transparency Reports, and participate in the Global Stocktake process. Countries are not legally bound to adhere to the content of their NDC, such as specific emission reduction targets, sectoral policies, or timelines. These content items are nationally determined and not enforceable internationally. There are no penalties for failing to meet NDC goals, and compliance relies on peer pressure, transparency, and global accountability mechanisms.

NDCs represent each country’s efforts to reduce national emissions and adapt to climate change. Countries are also invited to communicate voluntary “mid-century long-term low GHG emissions development strategies” (LTS & LTS-LEDS). NDCs and LTS are considered central mechanisms for achieving the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting global warming to well below 2°C and pursuing efforts to limit the increase to 1.5°C.

As of December 5, 2025, Climate Watch reported that 121 countries, representing an estimated 74% of Global Emissions, had submitted new NDC reports, leaving 76 countries that had not submitted an updated NDC. NDCs can include unconditional or conditional elements. Unconditional elements of an NDC refer to actions that countries commit to implementing using their own resources. In contrast, conditional elements are actions that are contingent upon international support (such as finance, technology, or capacity building). According to the World Resources Institute’s Climate Watch Platform, “many smaller and developing nations are leading the way with stronger targets, often conditional on international support.”[i] However, it should be noted that the praised “stronger targets” were conditional on receiving a cumulative $2.8 trillion in external funding!

Significant progress has been made in developing and operationalizing the NDCs as a core mechanism for identifying and implementing countries’ mitigation and adaptation targets. Countries report progress on their NDCs through the Enhanced Transparency Framework (ETF), which integrates national Biennial Transparency Reports. In addition, NDCs are the primary input for the Global Stocktake, conducted every five years, to assess collective progress toward the Paris Agreement’s temperature goals and to drive global action on climate change.

Practical tools have been developed to support countries in mobilizing their NDCs and their associated National Adaptation Plans (NAPs). The Global Implementation Accelerator offers support in technology, capacity building, finance facilitation, and pipeline development. The Belém Mission to 1.5°C for COP30 was introduced to help countries develop partnerships, sectoral roadmaps, increase accountability, and support vulnerable regions

Takeaway: According to a World Resources Institute (WRI) article published on November 12, 2025, the unconditional and conditional 2025 Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) submitted by over 100 countries so far are projected to achieve less than 14% of the additional emissions reductions necessary by 2035 to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. WRI further reported that 41 of the 108 developing countries submitting NDCs had noted financial requirements of $2.8 trillion to implement plans to achieve the 14% emission reduction by 2035.

Temperature Goals

The Paris Agreement, approved at COP21 in 2015, set a goal of limiting the global mean surface temperature, compared to a pre-industrial baseline, to well below 2°C, with efforts to limit the increase to 1.5°C. However, the global mean temperature last year was 1.55°C above pre-industrial temperatures. UNEP’s Emissions Gap Report 2025: Off Target noted that global warming projections over this century, “based on full implementation of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs),” are now estimated to fall in the range of 2.3-2.5°C[ii], while projections based on current policies would produce a temperature increase of 2.8°C. These temperatures are lower than those projected in last year’s report, but some of the improvement is due to methodological revisions. The 2026 withdrawal of the US from the Paris Agreement will eliminate about 0.1°C of improvement. According to UNEP, “the latest NDCs have barely moved the needle.”

Takeaway: The Paris Agreement, approved at COP21 in 2015, set a goal of limiting the global mean surface temperature, compared to a pre-industrial baseline, to well below 2°C, with efforts to limit the increase to 1.5°C. The world surpassed the 1.5°C target in 2024 and must substantially reduce projected greenhouse gas emissions if global warming is to be kept under 2°C.

Financial commitments, implementation mechanisms, and voluntary initiatives.

COP30 finance outcomes represent a mix of political commitments and voluntary pledges aimed at accelerating climate action. The financial commitments and voluntary pledges are not enforceable but are “political texts” under the UNFCCC and therefore not considered treaties. Compliance relies on transparency and reputational pressure, not legal penalties.[iii]

The summary below outlines the financing outcomes, including goals, implementation methods, and voluntary initiatives from COP30, presented in a concise format for the reader’s convenience.

New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG)[iv]

A $300 billion per year climate finance target was agreed at COP29. COP30 reaffirmed that amount in conjunction with the adoption of a New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) and its integration into UNFCCC mechanisms. The NCQG is a new framework for international climate finance, establishing a collective benchmark for financial flows to developing countries. The NCQG:

- Ensures a minimum of $300 billion per year in public climate finance by 2035, which includes tripling the Adaptation Fund to $120 billion per year;

- Aims to mobilize $1.3–$1.4 trillion annually of both public and mobilized private finance by 2035;

- Covers finance needs for mitigation, adaptation, and loss & damage;

- Serves as a political signal and accountability framework, though it is not legally binding; and

- Includes all UNFCCC funds (e.g., Green Climate Fund, Global Environment Facility, the Adaptation Fund, the Fund for responding to Loss and Damage) and mobilized private finance linked to public leverage.

Fund for responding to Loss & Damage (FRLD)

- The FRLD was confirmed at COP28 and reaffirmed at COP30 as an operating entity under the UNFCCC Financial Mechanism, serving both the Convention and the Paris Agreement.

- The FRLD is a formal UNFCCC financial mechanism established to provide new and predictable finance to help vulnerable developing countries address loss and damage caused by climate change.

- The Fund covers both economic losses (e.g., infrastructure damage) and non-economic losses (e.g., damage to cultural heritage and ecosystems).

- The Fund is guided by the Conference of the Parties (COP) and the Conference of the Parties serving as the Meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement (CMA) decisions; the World Bank hosts the interim secretariat.

- Funding Sources include contributions from developed countries and other donors; replenishment cycles (e.g., every four to five years) are similar to those for the Green Climate Fund.

- FRLD is included in the NCQG framework as one of the delivery mechanisms for loss and damage finance.

- Funding complements adaptation and mitigation finance by addressing irreversible impacts.

- The Loss & Damage funds are held in the FRLD trust. The first disbursement of $250 million from the FRLD trust is expected in 2025-2026 under the Barbados Implementation Modalities (BIM) for country-led proposals. BIM is the operational framework adopted at COP30 to govern the FRLD’s resource disbursement.

Voluntary Initiatives (outside of the NCQG)

The Belém Mission to 1.50C and the Tropical Forest Forever Facility were launched at COP30 to accelerate climate action. These initiatives did not require formal approval from the COP or CMA because they fall outside the UNFCCC’s framework. Associated funding does not count toward NCQG finance targets.[v]

Takeaway: Despite significant efforts and progress in implementing Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and establishing financing mechanisms, several concerning trends remain. These include ongoing divisions within and among countries regarding resource allocation, country-specific political challenges, national budgetary constraints, and difficulties in enforcing commitments. Additional concerns include the challenges in tracking and measuring outcomes, which raises the risk of underestimating significant, long-term gaps between funding aspirations and funding availability. The flexibility in payment schedules, which allows nations to postpone dispensing funding commitments, increases the risk of non-payment or partial payment. Delays in receiving funds result in the postponement of mitigation and adaptation efforts, which in turn lead to delays in climate change mitigation and adaptation actions.

Fossil Fuel Transition

The first formal recognition of the need to transition away from fossil fuels occurred at COP28. This recognition raised hopes that COP30 would develop and agree on a formal decision text outlining a roadmap for phasing out fossil fuels, complete with timelines and milestones that align with the 1.5°C goal, as well as identifying principles for an Integrated Just Transition that ensures equity.

The outcome in Belém disappointed many attendees. Participants could not agree on stronger language regarding fossil fuels. No roadmap for phasing out fossil fuels that aligns with the 1.5°C goal was adopted. This topic is likely to remain a contentious issue at future climate conferences.

Takeaway: The use of fossil fuels in the specified sectors accounts for 73% of total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Implementing fossil fuel-targeted strategies as soon as possible would be the most prudent course of action to achieve immediate results. Additionally, focusing on the efforts and actions of the top 10 countries that contribute the highest emissions—likely linked to fossil fuel use—should be another strategy worth evaluating.

Just Transition

There have been ongoing discussions about the need for a “Just Transition” from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources. These discussions focus on transitioning from a fossil fuel-dominated electricity production system to one based on renewable energy sources, such as solar, wind power, geothermal energy, and nuclear power. COP30 produced the Belém Action Mechanism (BAM), the first institutional framework under the UNFCCC to embed worker participation, labor rights, social protection and decent work into climate policy. Labor organizations celebrated the BAM agreement as a “historic victory for people power.” BAM is expected to ensure that indigenous peoples, youth and women’s groups, and climate justice activists will have a seat at future climate negotiations, facilitating a structural shift in climate governance.

The Potential Finance Gap between Aspiration and Actual Commitments

A country’s ability to meet its financing commitments depends on fluctuations in politics and national budget challenges. Additionally, any delays or deferrals of funding commitments will place more urgency on making up shortfalls in the later years of the 2035 cycle. Although the intent under the Paris Agreement was to build countries’ ambition and aspiration, there is a risk that the $300 billion per year agreed to be available from public climate finance by 2035 will not be met. Furthermore, the $1.3–$1.4 trillion annual request for both public and mobilized private finance carries an even higher risk of not being met.

Unresolved resource issues at the country level will undoubtedly affect global negotiations, increasing the likelihood that a consensus on funding cannot be reached. A key issue regarding climate action finance involves determining who should bear the costs of mitigation and adaptation. Should these costs be assigned to the historical or current contributors of pollution, or a combination of both? Additionally, the ability or willingness of donor countries to support countries without the resources to take effective action is a crucial element in this discussion.

Who should have a voice in decisions regarding the ownership and utilization of natural resources is also an issue. If national resources (leading to greenhouse gas emissions) are used to generate income or accumulate wealth, should they be shared, or should a financing mechanism be established to ensure their sustainability? Who owns these resources, and who are their protectors?

These issues and others will continue to hinder the generation of the necessary funding to implement the needed climate actions. We need to rethink the financing of climate actions so that we can provide a workaround for these underlying resource allocation issues. However, WellBeing International suggests that we take away the funding distractions at the country level and focus on a global funding strategy.

Takeaway: Resource allocation will continue to be a contentious aspect of climate negotiations for the almost 200 countries and regions, as they try to develop a “consensus” on acceptable funding amounts and mechanisms, which will delay the implementation process. Perhaps country-focused public support debates should be eliminated in favor of refocusing revenue generation based on global user fees. Such fees would be assessed and collected on all users of fossil fuels for each country. Every person would share the cost of the present use of fossil fuels, aligning users with those costs. This would remove climate action funding from increasingly contentious country budget politics, contribute to timely revenue flows, and support quicker implementation.

Implementation: Realignment, Refocus and Time Constraints

Prevention vs Cure?

“There are risks and costs to action—but they are far less than the long-range risks of comfortable inaction.” John F. Kennedy

Economic

- In 2015, a meta-analysis by the Center for Economic Policy Research of numerous models costing the effects of delays in addressing global warming, titled The Cost of Delaying Action to Stem Climate Change: A meta-analysis, reported that delaying the implementation of climate change measures could result in about a 40% increase in the net present value cost of addressing climate change.

- A 2022 IMF blog, titled Further Delaying Climate Policies will Hurt Economic Growth, reports that, based on economic modelling, delaying the transition to renewables significantly increases the macroeconomic costs of global warming compared to acting now.

Environmental

Many publications address the environmental impacts of continued inaction on climate change. In 2020, 11,000 scientists signed onto an article in Bioscience by William Ripple and four colleagues, which documented the Earth’s environmental climate emergency. The article reported that 22 of Earth’s 34 vital signs are reaching a crisis point. Others report that continued inaction could push global warming beyond 3°C, making the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C goal “completely out of reach.”

Takeaway: A rapidly growing body of research indicates that delaying climate mitigation is associated with substantial future increases in financial costs and negative sociopolitical consequences.

COP Realignment and Refocus

Attendance

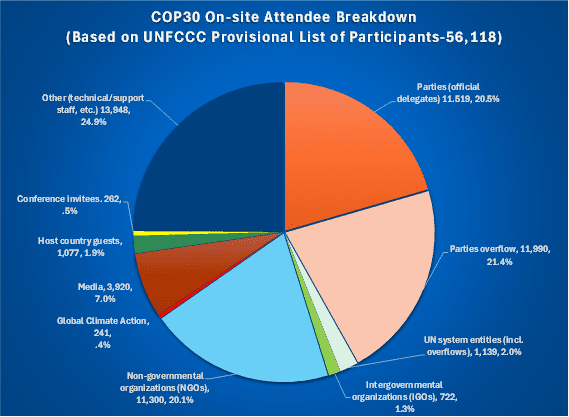

The attendance at each of the first eleven climate COP events was 10,000 or fewer; however, the numbers increased thereafter. COP28 had the highest attendance, with 83,884 participants. The provisional tally for COP30 on-site attendees stands at 56,519 plus 5,141 virtual attendees. The breakdown of COP30’s attendance is shown in the chart.

The total number of country representatives at Belém approached 24,000. There were almost 14,000 support staff and 11,500 NGO representatives. The remaining attendees were there to lobby decision-makers or report on outcomes.

While WBI examines decision-making processes, costs, and agendas, the topic of attendance merits its own discussion. The sheer size of these meetings raises questions about their effectiveness in advancing global decisions that involve nearly 200 countries.

Countries differ significantly in terms of GDP, their willingness and ability to pay, resource allocations, internal and external challenges, access to technology, and the presence of sensitive and contentious issues. Additionally, the complex topics that arise from these differences require careful negotiations, which may not be effectively handled in venues with such large numbers of on-site attendees, including thousands of external stakeholders from industry, media, and special interest NGOs.

Takeaway: COPs need a reimagining of how decision-making and the rapid implementation of necessary climate actions can occur more efficiently and effectively at future UN Climate Change Conferences, while ensuring adequate engagement and representation for indigenous groups, youth activists, NGOs, industry representatives, media, and other interested parties.

Agendas

The administration of the UNFCCC treaty, along with its subsequent protocols, agreements, and meetings, has led to a complex administrative structure. The annual COP acts as the main decision-making body of the UNFCCC. However, there are two additional decision-making bodies: the CMP for the Kyoto Protocol and the CMA for the Paris Agreement. The COP, CMP, and CMA meet concurrently during the same COP session and share the same Bureau (composed of representatives from the countries that are parties to each treaty) and Secretariat to enhance efficiency.

There have been 30 Conference of the Parties (COP) meetings, 20 Conference of the Parties serving as the Meeting of the Parties (CMP) to the Kyoto Protocol, and 7 Conference of the Parties serving as the Meeting of the Parties (CMA) to the Paris Agreement, each with its own agenda. The permanent subsidiary bodies of the UNFCCC, namely the Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technical Advice (SBSTA) and the Subsidiary Body for Implementation (SBI), provide recommendations, technical guidance, and decisions for adoption by the COP, CMA, and CMP. Each of these bodies traditionally meets twice a year and is currently in its 63rd sessional period, and each body has its own formal agenda.

Although each of the three governing bodies has its own agenda, they convene during the same COP meeting. The CMP’s agenda and activities are winding down. In contrast, the agendas for the COP and CMA have significantly expanded since the early years of the COP and are now multi-body, multi-track, and crosscut with topics from previous meetings. COP agendas focus on broader climate architecture, pre-Paris commitments, and convention-level finance and adaptation. In contrast, CMA agendas focus on implementing Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), carbon markets, and transparency and ambition targets related to the goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C.

The officers of the COP, CMP, and CMA are elected from the member parties of each treaty, which are the countries that have signed the agreements. Given the number of stakeholders involved in international climate negotiations, it is not surprising that the COP agenda has grown significantly since the first COP in Berlin in 1995. The expanding administrative structure for international climate negotiations, the diverse interests of successive COP hosts, and the existence of three separate yet interconnected decision-making bodies have all contributed to the expanded agendas. During the COP in Belém, Brazil, the same individual, Ambassador Corrêa do Lago, served as President of the COP, CMP, and CMA, a common practice.

The core agendas for the last 10 COPs include: Mitigation, Adaptation (Global Goal on Adaptation – GGA), Finance (New Collective Quantified Goal – NCQG), the Enhanced Transparency Framework (including Biennial Transparency Reports), Article 6 of the Paris Agreement (which establishes a framework for international cooperation and carbon markets), Loss and Damage, Just Transitions, Nature and Forest, Food Systems, and Oceans.

Takeaway: Observations regarding the agendas of the COP, CMA, and CMP illustrate the complexity of climate action. These discussions encompass a broad range of topics, including mitigation, adaptation, finance, and transparency, as well as cross-cutting themes such as just transitions and biodiversity. Each topic often gives rise to interconnected reporting obligations, such as the Biennial Transparency Reports under the Paris Agreement and the Global Stocktake cycles, which link national efforts to global assessments.

Opportunity Costs

As discussed in WBI’s October COP30 newsletter article, WBI believes that comprehensive cost accounting is essential to determine the full opportunity costs associated with hosting COP meetings over the past four years. The study should encompass the costs incurred by the host country, UN-related agencies, and all attendees. A thorough analysis of costs and benefits, as well as the relationship to implementation and alternatives to the current COP format, should be considered. Additionally, the evaluation should assess the implications of shifting the COP meeting to a permanent venue, as well as the frequency and format of satellite meetings (such as the annual June meeting in Bonn).

Takeaway: The UN must assess the total costs of COP meetings, explore alternatives to these conferences, and investigate how they impact the implementation speed of necessary climate change actions.

Consensus

It has become clear from recent COP meetings that achieving consensus on contentious issues among nearly 200 countries is a daunting challenge. As highlighted in a previous newsletter, there is no precise UNFCCC definition of consensus, resulting in varying interpretations by successive COP presidents. The large number of countries, each with their own diverse interests, further complicates the process. This difficulty in reaching consensus on contentious issues reduces the efficiency and effectiveness of climate actions and impedes the goal of accelerating implementation.

Takeaway: If the UNFCCC wishes to achieve its stated climate goals, WellBeing International argues that there needs to be a change in how decisions are approved (perhaps switching from consensus to a super-majority) and a streamlining of administrative complexity.

Final Comments

Implementation

There is an urgent need to accelerate progress on mitigating global warming. A fraction of a degree increase in warming may lead to irreversible ecosystem changes, as well as associated threats to human and animal well-being and global biodiversity. WBI promotes the following refocusing of climate actions.

WellBeing International recommends a refocus on the nine countries and the EU that are responsible for 70% of the world’s annual carbon dioxide emissions, measured in global equivalents, released into the atmosphere. This approach could potentially reduce emission levels quickly and reduce the reporting burden on some countries, as well as the UNFCCC’s administrative burden.

Fossil fuel use currently accounts for 73% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Fossil fuel production and use must be addressed to accelerate a reduction in global warming and mitigate climate change.

A reevaluation and refocusing of COP30 is needed. Attendance at COP28 exceeded 83,000, with over 53,000 attendees at the COP. The total opportunity costs for conducting these meetings are unknown. Extensive agendas were presented for COP, CMA, and CMP, which include complex topics, cross-cutting themes, and interconnected reporting obligations, with an evolving roadblock on decision-making due to consensus-based decision-making. These issues hinder swift decision-making and the timely implementation of climate actions.

Finance

The Paris Agreement aimed to enhance countries’ ambitions and aspirations regarding climate finance. However, there is a concern that the $300 billion per year commitment for public climate finance by 2035 may not be achieved under the new finance framework known as the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG). Additionally, the NCQG’s annual target of $1.3 to $1.4 trillion for both public and mobilized private finance is at an even greater risk of not being met.

Risk factors include ongoing divisions within and among countries regarding resource allocation, as well as specific political challenges faced by individual countries. National budget constraints and difficulties in enforcing commitments further complicate the situation. Additionally, concerns exist about challenges in tracking and measuring outcomes, which raises the risk of underestimating significant, long-term gaps between funding goals and actual funding availability. Delays in receiving funds lead to postponements in implementing mitigation and adaptation measures, which ultimately result in further delays in addressing climate change.

WellBeing International suggests that debates over public support in individual countries should be abolished. Instead, the focus should shift to generating revenue through global user fees. These fees would be assessed and collected from all users of fossil fuels in each country. By doing this, everyone would share the costs associated with their use of fossil fuels, aligning users directly with those expenses. This approach would remove climate action funding from divisive budget politics at the country level, ensure timely revenue flows, and facilitate quicker implementation of climate initiatives.

Complexity

The UNFCCC system is complex and multi-layered, having evolved over decades of institutional changes. Current agendas effectively showcase this complexity, addressing topics such as mitigation, adaptation, finance, transparency, and cross-cutting issues like transition and biodiversity. Each topic creates interrelated obligations and reporting requirements, involving various stakeholders and interest groups.

Compliments

WellBeing International emphasizes the need for global initiatives to combat climate change, suggesting that several revisions to the current global system are necessary. However, we understand the challenges in reaching a consensus among 200 countries regarding the best path forward. The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and its subsequent updates are significant achievements for the UN and its member nations. While there is still much work to be done, WBI acknowledges and supports all those who have made substantial progress so far!

Video credit: Anderson Coelho, iStock

[i] According to the World Resources Institute’s Climate Watch platform, “many smaller and developing nations are leading the way with stronger targets, often conditional on international support,” and most lower-income countries specify both unconditional and conditional targets in their NDCs. Climate Watch data shows that the majority of recent NDC submissions include conditional components, which aligns with estimates that roughly two-thirds of the 121 updated NDCs contain such provisions (Climate Watch, WRI, 2025).

- Climate Watch NDC Tracker: https://www.climatewatchdata.org/ndcs

- WRI Methodology Note on NDCs: https://www.wri.org/climate/ndc-enhancement

[ii] The global mean surface temperatures of 2.3°C and 2.5°C mentioned in the UNEP report are based on different assumptions regarding Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). The 2.30°C scenario assumes that both conditional and unconditional NDCs are fully implemented, while the higher 2.50°C scenario only considers the full implementation of unconditional NDCs. The actions associated with conditional NDCs depend on receiving international funding support.

[iii] Political texts in the context of COP decisions refer to formal statements adopted by consensus during UNFCCC negotiations that express political will but do not create legally binding obligations. In other words, the term “political text” has a very specific and non-obvious meaning in climate negotiations.

Key Characteristics of Political Texts:

- Adopted at COP sessions as part of the official outcome documents (e.g., “COP30 Decision Text”).

- Reflect negotiated positions and commitments agreed by Parties.

- Are non-binding under international law unless incorporated into a treaty or national legislation.

- Serve as guidance and signaling tools for future action, funding priorities, and cooperation.

- Compliance relies on transparency, reporting, and reputational pressure, not legal enforcement.

[iv] The New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) is a new global climate finance target of $300 billion per annum established at COP29 under the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement. It succeeds the previous $100 billion per year goal. It sets a collective benchmark for international climate finance flows to developing countries, aiming to:

[v] A brief description of these initiatives includes: Belém Mission to 1.5°C – a political and technical platform to drive ambition toward the Paris temperature goal, Tropical Forest Forever Facility – focused on forest conservation finance, Catalytic Capital for Agriculture Transition – aimed at sustainable food systems.

[vi] United Nations Environment Programme (2025). Emissions Gap Report 2025: Off target – Continued collective inaction puts global temperature goal at risk, Pg. 7, Figure 2.2, [Olhoff, A., chief editor; Lamb, W.; Kuramochi, T.; Rogelj, J.; den Elzen, M.; Christensen, J.; Fransen, T.; Pathak, M.; Tong, D. (eds)]. Nairobi. https://doi.org/10.59117/20.500.11822/48854.