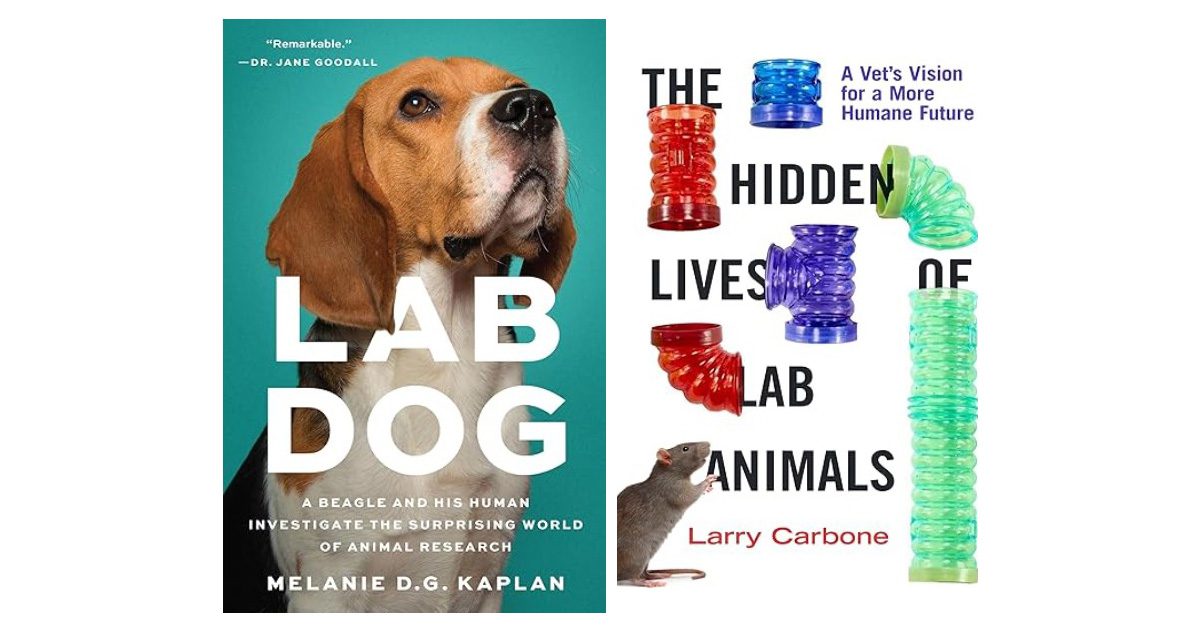

Jan 25, 2026 Book Review: “Lab Dog” by Melanie D.G. Kaplan and “The Hidden Lives of Lab Animals: A Vet’s Vision for a More Humane Future” by Larry Carbone

These two books deal with the same topic, animal research and testing, in quite different ways. Both describe very personal explorations of the topic, grounded in the two authors’ interactions with laboratory animals.

Melanie Kaplan, author of Lab Dog and a journalist, adopted a beagle, Hammy, who had previously been a laboratory animal. Curious about Hammy’s origins and previous experiences, Kaplan travels to interview numerous individuals representing various aspects of Hammy’s laboratory life, ranging from commercial breeders of beagles to research scientists using dogs to animal activists seeking to end research on dogs.

Melanie Kaplan, author of Lab Dog and a journalist, adopted a beagle, Hammy, who had previously been a laboratory animal. Curious about Hammy’s origins and previous experiences, Kaplan travels to interview numerous individuals representing various aspects of Hammy’s laboratory life, ranging from commercial breeders of beagles to research scientists using dogs to animal activists seeking to end research on dogs.

Larry Carbone, author of The Hidden Lives of Lab Animals: A Vet’s Vision for a More Humane Future, is a veterinarian who chose a career caring for laboratory animals, including many dogs. Indeed, one of the twelve chapters of his book is titled “Dog,” in which he opens the chapter by referring to dogs as the “everyanimal” during his four years in veterinary school, learning animal surgery and his clinical skills.

Kaplan travels across the country with Hammy in tow, interviewing people. Her relationship with the former lab dog is beautifully and tenderly portrayed. She explores the origins and life experiences of the average laboratory beagle, investigating how animals have been used in medical research, drug discovery, and the safety testing of drugs, cosmetics, foods, cigarettes, and pesticides. Each topic is accompanied by descriptions of specific cases and enriching interviews with relevant individuals.

Kaplan’s travels also led her to interview Dr. Larry Carbone, a laboratory animal veterinarian and the author of the other book being reviewed. In the introductory chapter, Dr. Carbone notes that he did not enter veterinary school with the intention of becoming a laboratory animal veterinarian. He is unique in this field because he is interested in the ethical arguments presented by philosophers and animal activists. While at Cornell, he pursued a PhD in the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology. To my knowledge, he is the only laboratory animal veterinarian in the world to hold a PhD in moral philosophy.

Kaplan delves into animal research to better understand her beloved Hammy’s origins and early experiences. In contrast, Carbone aims to make the reader aware of the complex scientific and ethical issues that laboratory animal veterinarians encounter. Carbone thoroughly examines the numerous challenges that both laboratory animal veterinarians and scientists face when deciding which animals to use in their studies and how to ensure the welfare of those animals is both protected and enhanced.

Carbone’s final chapter offers a list of suggestions for enhancing the US animal research system. Recommendation 13 emphasizes the importance of funding and promoting alternative technologies that do not use animals. To the surprise of many, the National Institutes of Health has established a special office to support this initiative. Additionally, both the Food and Drug Administration and the Environmental Protection Agency are working on developing methods that could eventually eliminate the need for laboratory animals.

For those interested in understanding how laboratory animals are used in medical research and chemical safety testing, reading both of these books will provide a comprehensive overview of current practices in animal research in the United States. They also discuss potential changes to animal use and the possibility of eliminating it in the future.

Nobel Prize winner in Medicine, Sir Peter Medawar, stated in 1969, “Only research on animals can provide us with the knowledge that will eventually allow us to eliminate their use altogether” (The Hope of Progress, 1972, p. 86). Medawar predicted that reliance on laboratory animals would decline within 10 years. In reality, this decline started in many industrialized countries in the mid-1970s.

Invasive laboratory research on chimpanzees has concluded, and invasive medical research on dogs will likely end soon as well. In the 1960s, up to half a million dogs were used each year in American laboratories for biomedical education, chemical testing, and medical research. Today, that number has declined to approximately 50,000.