Sep 29, 2023 Laboratory Animals and Non-Animal Alternatives

The 12th World Congress on Alternatives and Animal Use in the Life Sciences ran from August 27-31, 2023, at a hotel in Niagara Falls, Canada. There have been many advances in reducing and replacing laboratory animals since the first of these World Congresses, an initiative launched in 1993 by Dr. Alan Goldberg and held in Baltimore. During that first Congress, coauthor of the 1959 landmark text on alternatives, Dr. Bill Russell, treated the astonished attendees to a full-throated aria on “alternatives” set to a Gilbert and Sullivan song. Since then, additional Congresses have been held at different venues worldwide every two to three years. In 2001, the Alternative Congress Trust was established as a charity in the USA to help raise funds and to provide continuity and support for the organizers of later Congresses.

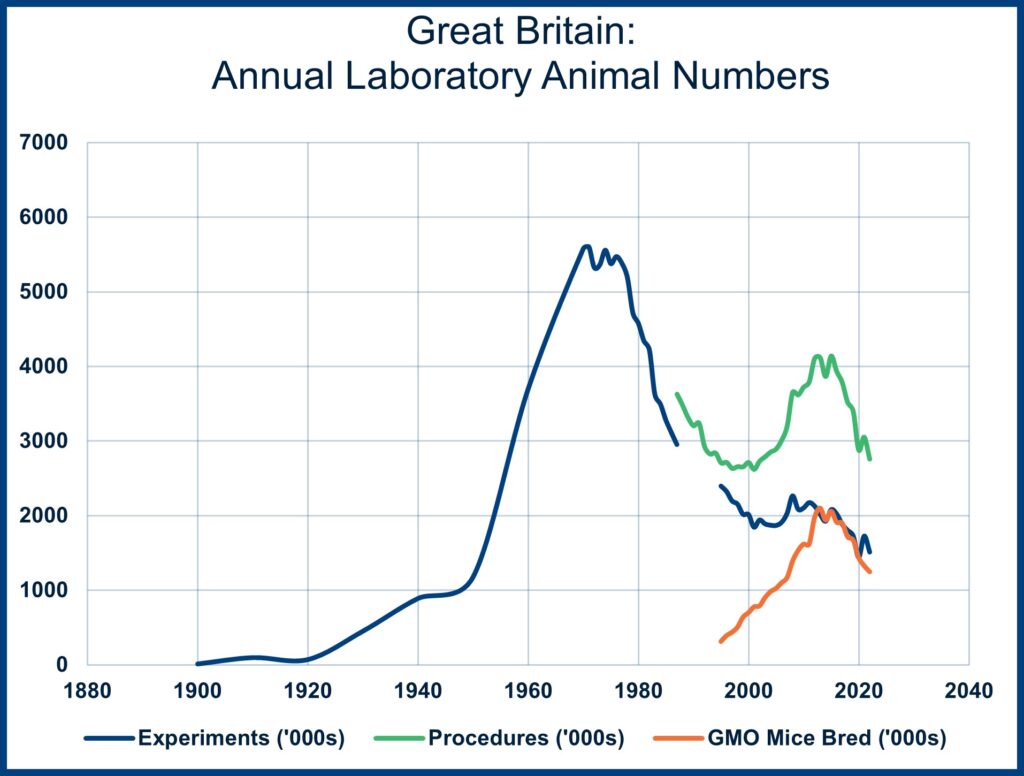

The chart below tracks the changes in laboratory animal use in Great Britain from the 19th Century to the present. It likely provides a window into laboratory animal use in Europe and North America[i]. As the chart indicates, there was a rapid increase in laboratory animal use after World War II, followed by an equally rapid fall from the mid-1970s to the early 1990s, when animal use started rising again.

This second rise in animal procedures (the number of experiments stayed relatively flat) lasted around 20 years. New gene-editing techniques permitted the breeding of genetically modified mice with specific disease profiles. From 1993 to 2015, millions of such mice were bred, expecting that research using them would lead to a better understanding of various challenging human diseases and possible new therapies. However, despite some positive advances, these new techniques still need to achieve their projected promise.

In 2019, the Wellcome Sanger Institute near Cambridge in the UK and the UK Medical Research Council announced they would close their two programs to breed genetically modified creatures. Despite dismay and criticism from the scientific community, Jeremy Farrer, the director of the Wellcome Trust, argued in one report that this development was a “positive story.” The staff at the Sanger were using fewer animals, partly because of the development of new tissue culture techniques, such as cell organoids using induced pluripotent human stem cells, that “made it possible to think about reducing the numbers of animal experiments.”

The switch to research using human cell cultures is a significant reason why mouse breeding and animal experiments are again falling in Great Britain. The number of mice bred and the total number of animal experiments began a new downward trend in 2015. The production of genetically modified organism (GMO) mice caused an upward trend in the total number of laboratory animal “procedures” from around 1995 to 2015. However, the actual USE of animals in “experiments” remained relatively flat and has been trending down since 2015.

The rise in mouse breeding (yellow line) that started in the mid-1990s led to an increase in the number of procedures but not in the number of experiments (where the laboratory animals were used in research and testing rather than being bred and maintained but not used).

The reported numbers of laboratory animals produced or used in Great Britain, the Netherlands, and Switzerland all show the same trends (peaking in the 1970s and falling after that). Only limited numbers (no estimates for the number of rats and mice used) are available in the USA. Still, the available American data on other laboratory rodents and rabbits shows a similar peak in laboratory animal use in the 1970s, followed by a steady fall. In 2020, the use of hamsters, guinea pigs, and rabbits in the USA was around 25% of their use in the 1970s.

The animal numbers are not the only measure to track positive developments in laboratory animal use and alternatives. In 2015, Innovation UK produced a landmark report highlighting the growing importance of NAMS (standing for either Non-Animal Methods or New Approach Methods). It urged the British government to provide more significant support for developing NAMs and the companies marketing NAMS technologies. Innovation UK partnered with the National Center for the 3 Rs to make £4 million available to drive the uptake of non-animal technologies. In the Netherlands, the National Advisory Committee on Animal Research (NCAD) was asked by the government to produce a report (published in 2016) outlining how the country might move towards achieving the ultimate goal of animal-free research and testing. The Committee reported that NAMs were already available to replace animal use in regulatory safety testing but that further technical progress was needed to replace animals in basic biomedical research. The Australian government has also produced a report extolling the benefits of non-animal technologies and recommending that the government stimulate and support further developments in this area. The opening paragraph in the document states that non-animal models should “improve research quality and productivity, strengthen sovereign capability, and generate new national revenue streams.”

The three reports from the UK, the Netherlands, and Australia, together with the 2007 US National Academies of Science report recommending a move away from animal methods in safety testing and chemical regulation, all point to the current sea change in laboratory animal use and adoption of NAMs. A new US entity (NCATS – National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences) within the National Institutes of Health system is funding the development and refinement of NAMs. In addition, recent US legislative initiatives involving the FDA and the EPA have emphasized the importance of NAMS and urged a move away from animal testing.

WellBeing International predicts that the global move from animal models will continue to gather momentum, leading to rapidly declining dependence on laboratory animals and significant improvements in the productivity and human relevance of biomedical research and chemical safety testing.

[i] There have been several changes in how the use of laboratory animals is tallied in Britain. The most significant change occurred in 1987 when the British Home Office switched from counting animal “experiments” (typically, the use of one animal equaled one experiment) to tallying animal “procedures.” A procedure included the use of animals in experiments and the breeding of animals for experimental use. The switch increased the annual tally of animals in research by around 20%. The number of animals being bred increased from a few hundred thousand in 1987 to about two million in 2012. The actual “use” of animals in experiments hovered around two million from 2000 to 2015, when experimental use started to fall again.