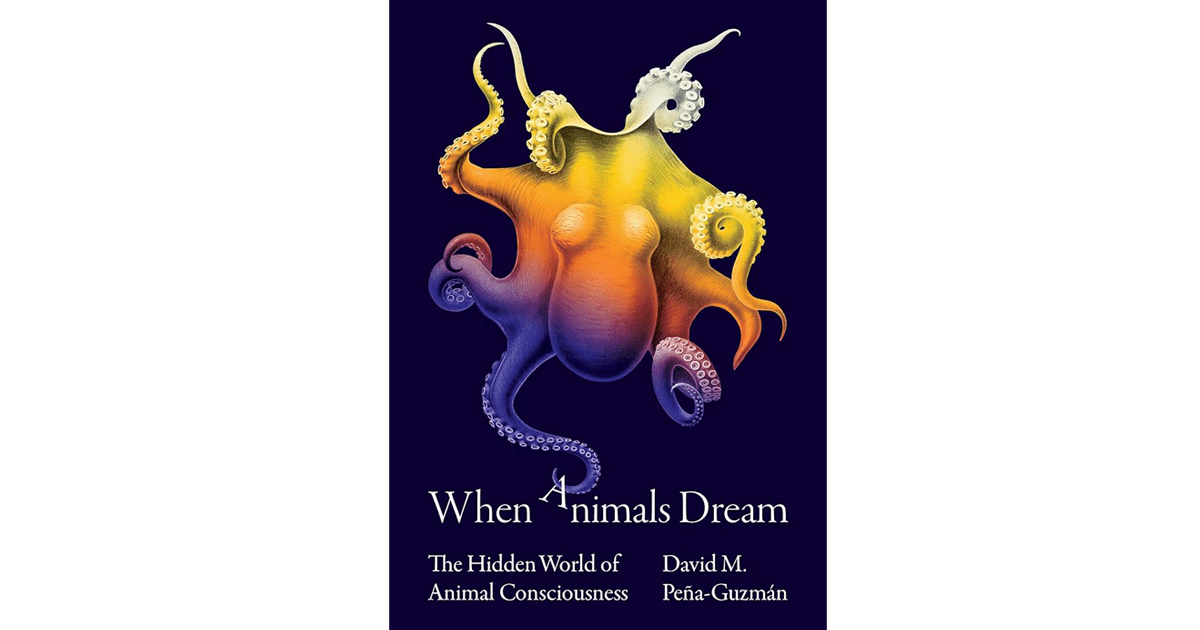

Jul 24, 2024 “When Animals Dream” – Exploring Consciousness and Ethics in David M. Peña-Guzmán’s New Book

Author David M. Peña-Guzmán, Ph.D., loves intellectual challenges. Previously, he wrote an article on whether or not animals can commit suicide, which has been downloaded over 44,000 times from the WellBeing International Studies Repository since its publication in late 2017. Now, the author has shifted his focus to investigating whether animals dream, which specific animals dream, and what implications it might have if animals have dreams like those experienced by humans.

The book, When Animals Dream, is divided into five chapters: “In the Trenches of Sleep,” “The Science of Animal Dreams,” “Animal Dreams and Consciousness,” “A Zoology of Imagination,” and “The Value of Animal Consciousness,” with an epilogue titled “Animal Subjects, World Builders.” In a discussion of the book, Peña-Guzmán observes that while there are numerous scientific publications on the sleep behavior of many species, very few of these publications in the 20th century mention the words “dream,” “dreams,” or “dreaming.” Peña-Guzmán suggests that the absence of references to animal dreams is symptomatic of an attempt to avoid the issue, and the current book endeavors to understand why animal dreams are missing from the literature on animal sleep and argues that this gap needs to be addressed.

The book certainly succeeds in describing the science underpinning his arguments that animals dream and the possible ethical consequences of demonstrating that animals dream. In the chapter on the value of animal consciousness, the author describes two types of consciousness – namely, access consciousness and phenomenological consciousness – and the moral implications of finding each type in individuals of other species. Briefly, access consciousness refers to “representational mental states whose contents are available … for use in executive functions such as reasoning, decision-making and linguistic reporting.” In plain English, a mental state is “access conscious” when we can think rationally about its contents, use those contents to make decisions about our future behavior and share them with others via language. Phenomenologically conscious states are more challenging to define and are not tied in any essential way to cognitive operations. Such states have certain feelings associated with them but do not represent anything in the external world. We find ourselves “in” a phenomenological state when we see, smell, taste, or experience pain, but those states are not “about” anything.

At this point, Peña-Guzmán puts his cards on the table and argues that phenomenal consciousness (not access consciousness) is what matters for any being to have moral status. However, many Western philosophers have placed access consciousness on a pedestal, concluding that humans have intrinsic value and are entitled to moral consideration because we are creatures who reason, behave rationally and communicate linguistically. However, British Utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham dismissed the ethical significance of reason and language 135 years ago when he commented on the acceptability of causing some beings pain, saying, “The question is not can they reason, nor can they talk, but can they suffer?”

Peña-Guzmán’s book is a wonderfully lucid examination of several extremely challenging biological and philosophical issues. I will likely re-read the book or parts of it several times in the coming year. What should we conclude when Heidi, the octopus, while asleep, progresses through a series of color changes that mimic how she might behave when catching and eating a crab? Or what about when chimpanzees who have been taught sign language start signing while asleep? Closer to home, what about the family pet that starts twitching and whimpering while asleep? Pena-Guzman provides many other examples of animal sleep behaviors and argues that the most parsimonious interpretation of those behaviors may be that the animals are dreaming. If he is correct, the conclusion that animals dream has significant ethical implications for how such animals are treated while they are awake.