Mar 14, 2022 The Magic of Being Among Gorillas in Rwanda

It was to be the trip of a lifetime. For decades, I’d imagined how thrilling it would be to walk among the Mountain Gorillas in their natural habitat. I’d been on several safaris elsewhere in Africa. Those were amazing, transformational experiences, yet there were still barriers. In Kenya and Tanzania, tourists viewing wild animals come collectively by the dozens, and one rarely leaves the safety of one’s vehicle. Even in Botswana, where the camps are small and remote and the experience more personal and direct, safaris lacked the allure of trekking with just a handful of others, on foot, into the realm of the Mountain Gorilla.

Even with such long and lofty anticipation, this trip didn’t disappoint. It was magical.

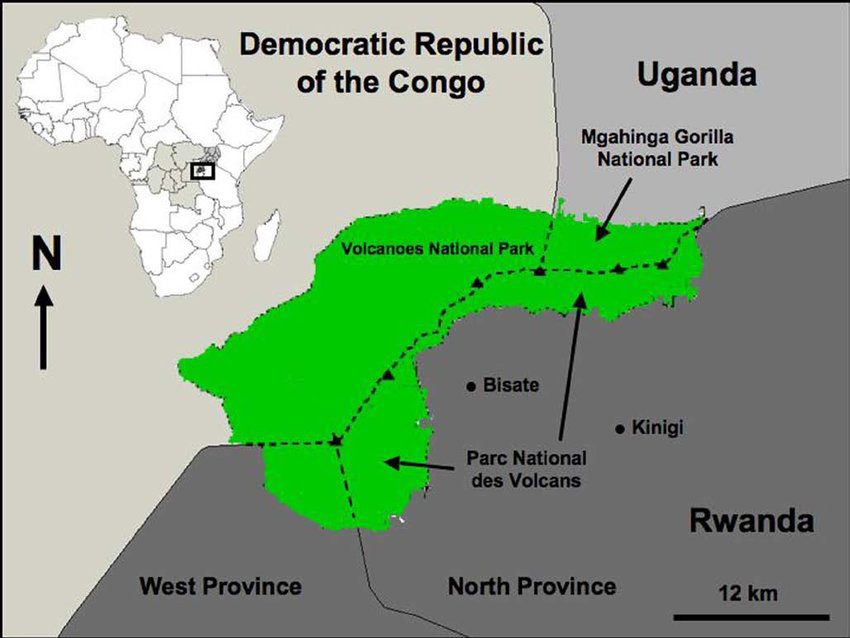

Figure 1 of Roelke and Smith (2010). Roelke, C. E., and E. N. Smith. 2010. Herpetofauna, Parc National des Volcans, North Province, Republic of Rwanda. Check List 6 (4):525–531.

The Mountain gorillas in Rwanda’s Volcanoes National Park are not just international celebrities. They are also actors in an all too rare conservation success story. Dian Fossey arrived in Rwanda in 1967 to study gorillas when the gorilla population in the Virunga Mountains ecosystem was declining. In 1972, the first complete census reported there were only 275 gorillas. The number of gorillas dropped to 254 by 1981. But it then started to grow thanks to the intensive monitoring of gorillas by Dian Fossey and her rangers. Monitoring continued after Fossey’s murder in 1985, and the gorilla population continued to grow to 320 individuals in 1989, 380 individuals in 2003, and 480 in 2010. The latest census reported 604 gorillas in Rwanda.

A critical factor in the growth of the gorilla population has been the development of a careful and very successful ecotourism industry to visit the gorillas in their “homes.” The project developed slowly as concerns about the impact on the gorillas and their conservation were addressed. Gorillas, for example, are susceptible to the same diseases (including Covid) as humans. Nevertheless, a recent study found that the habituated gorilla population grew at an annual 4.1% rate compared to a slight decline in numbers for those not habituated to a human presence. The researchers concluded that intense, conventional conservation efforts might prevent a decrease in gorilla numbers, but the population only grew where conservation was accompanied by habituation.

In Rwanda, pervasive care is taken to protect the gorillas. All humans are tested for Covid upon arrival in Rwanda and before trekking begins. A visitor’s permit is required to enter the Volcanoes National Park, and daily visitors are extremely limited in number. There are 12 gorilla families in the area we visited, each comprising 10-20 gorillas. Only one group of tourists may visit each family per day. The groups are generally limited to five or six human visitors. Visits are strictly limited to just one hour in the gorillas’ presence. All visitors wear masks at all times when near the gorillas. The treks are carefully supervised, monitored, and timed by guides who work for the Rwandan government. The gorillas are habituated, but they are not overexposed, endangered, or interfered with by human visitors.

The terrain in Volcanoes National Park is a thick, mountainous jungle. Without a guide, hacking a pathway with a machete would be extremely difficult to get through. Because the gorillas move significant distances every day, it would be impossible to find them on one’s own. The problem is solved by a group of trackers who follow the gorillas and bed down near them when they settle down for the night. The trackers radio their location to colleagues who guide the tourists the next day. The new tracker group replaces the old one for the next day. It’s a simple system that works remarkably well.

It took us approximately two hours to reach the gorilla family we’d been assigned. The gorillas were indeed habituated in the critical sense that our presence did not disturb or upset them. They ignored us and carried on their lives, eating bamboo shoots and leaves, the younger gorillas playing and play-fighting, a setting that was overwhelmingly tranquil and compatible with nature.

During our visit, our small group came into a clearing where we were surprised by a gorilla coming out of the brush right in front of us. This gorilla was followed by a 500-pound Silverback, who passed just inches in front of us. It was a breathtaking moment, thrilling, majestic, and a bit terrifying. The power of these animals is palpable, dominant, and absolute.

We went back a second day to visit another gorilla family, and we were treated to a full range of their daily activities. These activities included climbing trees, finding, cleaning, and consuming an endless array of branches and leaves, various episodes of play, and even some sexual behavior. Some disputes had to be resolved by the Silverback while moms and babies clung to each other. It is impossible not to sense our genetic kinship to these magnificent beings.

At one point, a gorilla came down from a tree and walked away, passing right in front of me. To my shock, but also to my absolute delight, when the gorilla passed me, he reached out and gently (but firmly) embraced my leg with his huge hand. It wasn’t aggressive, but it was not accidental, either. It felt so clearly as though he were saying hello, or just connecting with a brief but friendly touch the way we sapiens often do.

Credit: Google | CNES / Airbus, Maxar Technologies, Map data 2022

Gorilla ecotourism has provided significant benefits to Rwanda and the communities bordering Volcanoes National Park. These communities are among the densest rural communities globally – over 800 persons per Km2 – but despite human population pressures, the gorillas are now doing well. The image shows a slice of the Virunga Mountains and the sharp boundary between the park and agricultural land. The white line is the border between Rwanda (on the right) and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Part of the Virunga protected area is also in Uganda to the north. The latest census reported that there are now 1,063 gorillas in the Virunga park system in the three countries.

The history of human-gorilla interaction has been violent, short-sighted, and profoundly depressing. (The famous film of Dian Fossey’s experiences in Rwanda, Gorillas In The Mist, is worth another watch after all these years. So, too, is the more recent 2014 documentary, Virunga, which chronicles the brave efforts of some locals in the Democratic Republic of Congo to save and protect these mountain gorillas against poaching, land exploitation, and politics.

Today, Rwanda has fully embraced its good fortune to have these gentle, majestic animals in their midst. A new research, science, and visitor’s center opened last month there, built with the support of Ellen DeGeneres and others. Some American and European zoological societies are working with and supporting the “Gorilla Doctors,” a cadre of local veterinarians committed to the difficult task of keeping the gorillas healthy while still living in the wild.

There’s a reason for cautious optimism and every reason to partake, if one can, of the brief, magical moment that visiting the gorillas in their home affords.

Eric “Rick” Bernthal is a member of the WellBeing International Board. He practiced law in Washington DC for over 40 years and served as the Managing Partner of Latham & Watkins’ D.C. office for more than a decade. He has served on more than a dozen boards of organizations dedicated to animal welfare and advocacy. Living bi-coastally, Rick frequently drives across the continental United States with his rescue pit bull, Ollie, who provides essential navigation support.