Apr 30, 2020 Sustainable Development & Trophy Hunting

Posted at 07:54h

Sustainability has become a popular term encompassing the notion that we need to promote and pursue policies that will allow future generations of humans to live and benefit from the wealth provided by the Earth. In 2015, the United Nations (UN) adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development that identifies 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) emphasizing, in the words of the UN, “a holistic approach to achieving sustainable development for all.” This is a huge and hugely ambitious project, and it is astonishing that the world has been able to unite behind it through the agency of the UN. The complexity and ambition of the SDGs can be appreciated by scanning the 169 targets and 232 unique indicators that have been established to track progress. ‘Our World in Data’ at Oxford University has now set up an SDG Tracker where progress towards the SDG targets can be followed. A few minutes browsing this tracker (seven of 10 targets for Life in the Oceans and five of 12 for Life on Land do not have data that can be used to track progress) indicates just how complicated this initiative is. It is not possible to describe and evaluate even one of the SDGs in a brief essay, so we will look at only one tiny aspect of the sustainability question – namely, a recent discussion of trophy hunting in the media.

Ref- See pg. 35 of Chardonnet report.

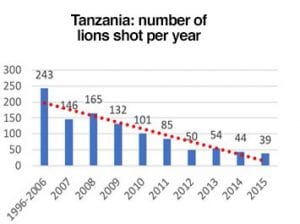

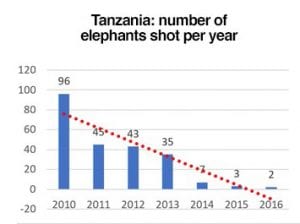

In 2019, Bertrand Chardonnet, a veterinarian with extensive experience in Africa (he has worked in 40 African countries), produced a report for the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) on reconfiguring the protected areas of Africa. He pointed out that trophy hunting in Tanzania had mostly collapsed (see figure of lions shot per year). The number of elephants shot also declined dramatically (see figure below).

Ref- See pg. 35 of Chardonnet report.

Elsewhere, the number of trophy hunters visiting South Africa had dropped from 16,549 in 2008 to 6,539 in 2016. Don Pinnock, a South African journalist who has argued against trophy hunting in his writings, produced an article that drew heavily on the Chardonnet report, published in the Daily Maverick on 30 April 2019, entitled “Trophy Hunting, Part Two: End of the Game.” His article argued that trophy hunting in Africa was on its way out.

This prompted a response from a number of people, including representatives of hunting organizations and members of the IUCN Sustainable Use and Livelihoods Specialist Group. The response “clarified” that the Chardonnet report was commissioned by an IUCN section to stimulate discussion only and that IUCN policy, described in an earlier 2016 briefing paper, encouraged trophy hunting because of its conservation and livelihood benefits. They further argued that the report was about the future of protected areas rather than trophy hunting per se, as if that invalidated the data on trophy hunting trends and economic returns in the Chardonnet report. Their response also argued that the decline in trophy hunting in Tanzania was largely due to a ban on trophy imports instituted by the United States, despite the fact that the bulk of the decline in trophy animals shot occurred before the US instituted bans on trophy imports.

Chardonnet argues that protected areas in Africa require an average of $7-$8 per hectare to manage successfully and that trophy hunting concessions typically bring in a tiny fraction of that figure. The Bubye Conservancy in Zimbabwe has been promoted as an example of the conservation benefits of trophy hunting. It is true that Bubye, which was established in 1994 by a wealthy investor, has restored wildlife to what was once a denuded and over-exploited cattle ranch, and that its lion population has gone from zero to around 500 (amongst the highest lion densities in Africa) with associated increases in other wildlife. But even in Bubye (which does spend around $7-8 per hectare in maintaining the 370,000-hectare conservancy), only around 33% of the annual running costs are generated from lion trophy hunting.

After the shooting of Cecil in Zimbabwe in 2015, trophy hunting has been under siege. It has been associated with several unsavory practices (e.g. the breeding and shooting of lions in “canned” circumstances in South Africa and government corruption). It is also a consistency problem to allow wealthy international visitors to shoot a few wild animals while local residents are prosecuted for poaching when they trap and kill animals. Chardonnet argues in his report that trophy hunting does not produce sufficient income to pay for proper conservation of wild lands. He further notes that these lands will be under increasing human pressure as the African population grows from 1.2 billion today to a projected 4 billion in 2100.

WBI called for an end to the consumptive use of terrestrial wildlife at a Conservation Geopolitics conference in Oxford (March, 2019). At the very least, we should end the killing of terrestrial wildlife for frivolous (e.g. trophy hunting) and luxury (e.g. ivory, rhino horn) purposes and build a consistent message that wildlife needs to be protected and not traded or killed, no matter the potential short-term benefits. Trophy hunting fees will not save wildlife and we need to construct new systems and policies that will produce a land ethic and sufficient economic resources leading to a truly sustainable future for the relatively few remaining wild places and the animals that inhabit them.

Note: the figures above are taken from page 35 of the 2019 report by B Chardonnet on Reconfiguring the Protected Areas in Africa. The report was commissioned by the IUCN but is not an official IUCN document. Additional documents addressing trophy hunting and sustainable use are available on the IUCN website.