Jan 17, 2022 Saving Tigers in America: Part 2

Tigers, Tigers Everywhere. The USA Tiger Sanctuary Challenge

As previously reported in WellBeing International’s Saving Tigers in America Part 1, the number of tigers held in the United States of America (USA) began to increase in the 1980s, driven primarily by the profit motive of entertainment and commercial ventures. Major zoos had discovered the attraction of newborn animals, especially tiger cubs, and had expanded their tiger breeding. The tiger supply soon exceeded the ability of the major zoos to house them, and old tigers were sold to roadside zoos and private owners to make room for cubs. A dealer network evolved, and 44 states wound up with tigers. Some exhibitors allowed one to hold a cub for a picture, advertised as “cub petting.” Cub petting quickly became a primary revenue stream. Cubs, however, become too dangerous to handle when they are about 100 days old. Continuous breeding became necessary to feed the demand for cubs.

The demand for white tigers also drove breeding. Only 1 of 30 tigers are born white. The rest are orange and sell for a few hundred instead of a few thousand dollars. The constant quest for the high-value whites also contributed to the ever-expanding tiger population. While there is little data on the expansion of tiger supply and demand during this period, tiger breeding (and hence supply) increased through the 1990s and got to the point where tigers became a commodity. Anybody who wanted a tiger for exhibition or as a pet could buy one.

In the 2000s, when technology made every phone a camera and the rise of social media created a demand for content, cub “petting” became cub “playtime.” One could now hold, feed, walk, run or swim with a tiger cub for $20 to $300 and capture one’s experience in a photo or video. Breeding continued because there is no limit to the number of tigers an individual or institution can own.

So, who are the primary holders of tigers today? One can classify tiger owners into four basic categories defined by their stated purpose: Entertainment, Pets, Conservation & Education, and Protection.

Entertainment – Approximately 2,000 organizations are licensed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to exhibit animals. According to Tigers in America (TiA), 300 of these organizations are “roadside zoos” holding approximately 2,500 tigers. In addition, circuses and safari parks, commercial operations using tigers to attract customers, and trainers supplying tigers for advertising keep a few hundred more. Again, the lack of accurate reporting data on tigers held by these facilities hinders an exact count.

Pet Tigers – Private ownership is banned or requires a permit in all but four states (Alabama, Nevada, North Carolina, and Wisconsin). However, private owners ignore the permitting process entirely or acquire the USDA exhibitor’s license in many cases. In 2010, authorities in Ohio attempted a census of privately owned big cats in the state but stopped the count when they reached 1,000! There are probably many thousand “pet” tigers in the USA. Whatever the reason somebody may want a pet tiger, it often does not benefit the tiger. One story of what happens when private ownership fails is provided below.

Conservation & Education – As noted in Part 1 of this series, in the 1960s and 1970s, a few major zoos began breeding tigers. Back then, zoos used tiger cubs to increase attendance, and a considerable number of tigers ended up in unaccredited roadside zoos. Today, major zoos are much more careful about tiger breeding. Approximately 100-120 members of the Association of Zoos and Aquaria (AZA) hold between 350 to 450 tigers, most of whom are part of a Species Survival Program (SSP). The tiger SSP now breeds tigers to maintain genetically diverse populations of three of the six remaining tiger subspecies – Amur, Sumatran, and Malayan tigers – and frown upon breeding outside the SSP program.

Protection – Many organizations (80-100) set themselves up as sanctuaries (charitable NGOs) to protect rescued exotics. There are no restrictions on using Sanctuary, Rescue, or Refuge in a corporate title. Many organizations using these terms are thinly disguised breeders or exhibitors. TiA defines a sanctuary as a facility that provides lifetime care in a sufficient space, with medical care, and that does not permit breeding, buying, selling, public handling, or taking the tiger off-site. TiA identified and works with 15 sanctuaries that currently can care for 500 to 600 tigers. This capacity represents considerable growth in the last twenty years. In 2001, nine TiA partner sanctuaries had an annual income of $3.9 million and net assets of $5.5 million. In 2019, these same nine organizations had annual revenue of $42.5 million and net assets of $63 million.

What happens when a Sanctuary fails?

The Wild Animal Orphanage (WAO) story – a Texas facility – provides insights into the risks when facilities claiming to be sanctuaries are mismanaged.

In 2003, Sullivan County in New Jersey clamped down on the private ownership of dangerous exotics. As a result, 24 tigers were sent to WAO. The founders of TiA, Bill Nimmo and Kizmin Reeves, had met seven of those tigers a few years earlier when they visited the New Jersey couple who owned them. The closing of WAO in 2010 (after 17 years of operation) led to a crisis for their 400 animals, including 55 tigers. This crisis led to Nimmo and Reeves’ decision to offer help. They were particularly interested in the fate of the New Jersey tigers shipped to WAO. The paper records were poor, so another way had to be found to determine if any New Jersey seven were still alive.

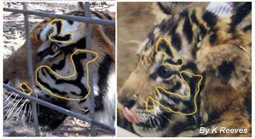

Fortunately, each tiger has a unique stripe pattern (akin to a fingerprint). Reeves compared the stripe patterns of the tigers she had photographed in New Jersey with pictures of the surviving WAO tigers. Pictured right. Three of the seven tigers had stripe patterns that matched the three cubs they had known in the late 90s – Amanda, Andre, and Arthur. They were housed at the back of the WAO property because they were so aggressive and the least likely to be placed. Despite this, TiA found a sanctuary in Florida willing to take them, and TiA agreed to fund their care. In September 2011, Nimmo and Reeves went to Florida to welcome the tigers they had known as cubs 15 years earlier. A reunion led to their discussions about setting up a tiger rescue organization.

Fortunately, each tiger has a unique stripe pattern (akin to a fingerprint). Reeves compared the stripe patterns of the tigers she had photographed in New Jersey with pictures of the surviving WAO tigers. Pictured right. Three of the seven tigers had stripe patterns that matched the three cubs they had known in the late 90s – Amanda, Andre, and Arthur. They were housed at the back of the WAO property because they were so aggressive and the least likely to be placed. Despite this, TiA found a sanctuary in Florida willing to take them, and TiA agreed to fund their care. In September 2011, Nimmo and Reeves went to Florida to welcome the tigers they had known as cubs 15 years earlier. A reunion led to their discussions about setting up a tiger rescue organization.

The lead image shows the three tigers resting in their sanctuary in Florida. Amanda, in the middle flanked by her two brothers Andre and Arthur, was dominant and was very protective of her two brothers. Amanda lived to be 23 (old for a tiger).

WAO failed because of squabbling among the founders and because of poor management. But the reasons for the failure were less critical than the lack of meaningful oversight. The collapse also illuminated the lack of standards for a “sanctuary.” In the end, 20 of the 55 tigers at WAO wound up dead or missing during the rescue despite the best efforts of animal rescuers.

What happens when a Private Owner has a dreadful day?

A facility’s mismanagement and failure are only a minor part of the surplus tiger challenge. The Zanesville, Ohio case provides one of the more tragic examples of what could go wrong.

On October 18, 2011, Dolly Kopchak of Zanesville called the local sheriff’s office because her son had locked himself in their barn after Terry Thompson, a neighbor, released his menagerie of 55 exotic wild animals, including 18 tigers and 17 lions. This call was the thirty-ninth such call received by the sheriff about Thompson, but this one was different. Deputies arrived to find tigers circling Dolly’s barn and discovered that Thompson had released all his animals and then had killed himself. Over the next fourteen hours, the deputies hunted down and killed 50 of the 55 animals. TiA founders were in Ohio at another rescue the month before. The Zanesville tragedy was the final stimulus leading to the establishment of TiA in November of 2011.

Large Scale Rescues become possible!

A few years later, TiA became involved with another case involving a roadside zoo and cub-petting operation near Colorado Springs in Calhan. Serenity Springs was typical of places where one could go to have one’s picture taken with a tiger cub. When launched in 1993 by Karen Sculac, the operation was an aspiring sanctuary. However, Karen died unexpectedly in 2006, and her husband took over. By 2015, Serenity Springs was still listed as a sanctuary but was now a full-blown tiger breeding, selling, and cub-petting operation. It was also for sale. TiA, partnering with another sanctuary in Arkansas, bought Serenity Springs and all of the 114 animals on the property, including 74 tigers. All the animals were relocated to TiA partner sanctuaries, and the property was then sold.

Sawyer in her new home.

Serenity Springs’ most emotionally damaged tiger was a young female named “Chainsaw.” She had been acquired from Joe Exotic (The Tiger King of the Netflix documentary). She never rested in the presence of people and charged the fence if any male human approached. She was in the last group that moved out of Serenity Springs to PAWS (Performing Animal Welfare Society) in California. PAWS is regarded as one of the most successful TiA partner sanctuaries in the country.

Two months after her arrival, TiA received an update on Chainsaw from Ed Stewart and Dr. Gai at PAWS. Her name and her life have changed. “Sawyer” now spends a lot of time relaxing in the sun on her favorite platform that overlooks a valley of tall grass. She had begun to greet all PAWS caregivers with a welcoming “chuff.” She is finally home and at peace.