Dec 16, 2021 Saving Tigers in America – Part 1

There are somewhere between 5,000 and 10,000 tigers in private hands in America today – one estimate is that there are 7,000 privately held tigers or around twice as many as the total population of wild tigers (approximately 3,900) in the world today. None of the tigers bred and raised in America have ever been put back into the wild. Instead, most of them spend a few months as cubs generating fees for their owners from cub-petting and photo operations and then spend the rest of their lives in cages, most of them in poor to mediocre conditions. A new organization, Tigers in America (TIA), was established in 2011 specifically to save the tigers in America. The first of a three-part series, this article describes the history of how America arrived at this point.

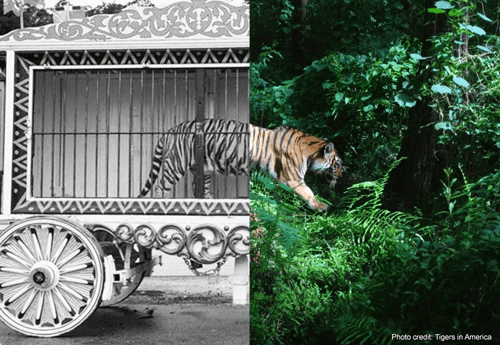

Tiger in a roadside zoo, 2003

Tigers have been present in America for almost 200 years. The first tigers and other non-native animals were delivered by sailing ships to Boston. These animals traveled up and down the east coast in makeshift cages, thus launching exotic animal exhibitions. In 1833, in a small town outside of New York, animal trainer Isaac Van Amburgh entered a tiger’s cage and dared the animal to attack. Amburgh’s fame spread, and he eventually became an international celebrity. Queen Victoria was particularly fascinated by his act. The success of his show led to tigers becoming a major attraction in the most profitable venture in the exhibition business at the time – the traveling circus. Upon Amburgh’s death, Ringling bought the rights to his act while competing circuses also rushed to establish tiger acts. At its peak in the 1920s, more than twenty circuses were touring the country, some in 100-car trains.

In the 1930s, primarily due to the depression, circuses began a slow but steady decline as movies, and then television became competing forms of entertainment. However, a decrease in circus tiger numbers was offset by an increase in tigers in zoos. Unlike the circuses, which bought their tigers from animal dealers in Europe (primarily Carl Hagenbeck in Hamburg), the American zoos started their tiger breeding programs.

Private ownership and private breeding of tigers remained rare in America until the late 1960s, when three seemingly unrelated events changed the fate of captive tigers in the country. First, in 1967, Irving Feld and his brother bought the Ringling circus. They immediately signed Gunther Gebel-Williams, who had a tiger act in Germany, to a contract. After shaving his goatee, dying his hair blonde, and putting on a sparkly costume, Gunther became Ringling’s headline attraction in America – the twentieth-century equivalent of Isaac van Amburgh.

Tiger in a roadside zoo, 2003

For 20 years, Gunther toured for Ringling, performing approximately 12,000 times (averaging almost two performances a day!). He never missed a show. With promotional abilities equal to P. T. Barnum’s, the Feld brothers transformed Gunther from an animal handler into a celebrity trainer. The circus was no longer just a traveling carnival. Ringling was reborn as mainstream entertainment, complete with a celebrity who appeared on talk shows. The main circus draw was now the man with the tigers. When Gunther retired, a series of animal trainers attempted to follow in his footsteps but could not emulate Gunther’s success.

Second, also in 1967, Siegfried and Roy, a magic act with card tricks and a live cheetah, arrived in Las Vegas. Their timing could not have been better. At the time, Las Vegas was attempting to transform its image from a gambling and burlesque venue to a city offering family entertainment. Siegfried (the magician) and Roy (the animal trainer) were a perfect fit and were an immediate sensation.

Their act initially involved just one cheetah, graduating to a single orange tiger and then eight white tigers. They became the highest-grossing act in the history of Las Vegas. Roy pushed celebrity and danger to a higher level and began working without a cage in front of a live audience, often guiding his tigers with only a leash. Over 35 years, more than 10 million people saw their show, and a whole generation of Americans grew up believing tigers, especially white tigers, were performing pets. The concept of private ownership of tigers and other big cats took root. But the appeal came to a sudden and tragic end when, in 2003, during a performance, one of Roy’s tigers bit him on the head, leaving him disabled and ending the show’s remarkable run.

Third, in the late 60s, the Cincinnati Zoo, an accredited member of the Association of Zoos and Aquaria (AZA), began breeding and selling white tigers to other zoos. Ed Maruska, the zoo head, extolled the value of the white tigers in stimulating zoo attendance as people flocked to see the white tiger cubs. However, when the cubs became adults, they were taken off-exhibit to make room for new cubs. When the off-exhibit area was at capacity, the tigers were classified as surplus and shipped to unaccredited roadside zoos. Many of the initial Siegfried and Roy white tigers came from the Cincinnati Zoo. [In 2011, the AZA prohibited breeding white tigers and other predator color morphs.]

By the 1980s, the transformation was complete. Tigers were no longer animals captured in the wild; they were a commodity, born and bred in the USA solely for their entertainment value. Despite the intentions of the tiger Species Survival Plans (SSPs), no tiger born in this country has ever been introduced into the wild. Instead, a network of backyard breeders has developed outside the zoo community to provide a continuous supply of tiger cubs.

In the 1960s, having one’s picture taken with a tiger involved a stationary camera and a small enclosure with a tiger that was usually declawed, defanged, and chained to a rock. Today, when every smartphone is a camera, photos with tigers have become big business. A tiger cub used for such photo opportunities could generate as much as $1,000 a day. However, the photographic life of the cub is only 90 days, at which point it weighs forty pounds and could kill a child. Three-month-old tiger cubs usually find their way to an unaccredited roadside zoo while the photographic center buys or breeds more cubs.

Quiet spaces at sanctuaries provide tigers a place to live free from the obligation to perform. While the past mistakes cannot be undone, TIA is helping to save tigers in America and, with their partner sanctuaries, providing a better future by rescuing tigers from bad situations and relocating them to true sanctuaries.

Tigers in America (TIA) is a nationwide, all-volunteer organization that operates from New York City. It has recently expanded its mission to accommodate the surrender or seizure of all big cats, including lions, leopards, mountain lions, cheetahs, and jaguars, in addition to tigers.