Jun 10, 2024 Healthy Brains, Scientific Innovation and “The Endless Frontier”

In 1945, Vannevar Bush, a key figure in the history of scientific research, sent a report to President Truman, Science- the endless frontier, advocating for an expansion of Federal funding of basic research and support for students seeking a college education. The committee advising Bush championed the provision of opportunity for all. It recommended, “that there be no ceilings, other than ability itself to intellectual ambition …every boy and girl shall know that, if he(sic) shows that he has what it takes, then the sky is the limit.” Five years later, Congress established the National Science Foundation, leading to a significant increase in funding for basic research. For example, in 1950, the National Institutes of Health received around $50 million in federal funding. Today, that figure stands at around $50 billion, showcasing the enduring impact of Bush’s vision.

The significance of supporting fundamental research and the advancement of new scientific technologies is demonstrated by the evolution of Developmental Neurotoxicity (DNT). In 2004, when the Johns Hopkins Center for Alternatives to Animal Testing (CAAT) initially began exploring non-animal technologies to evaluate chemicals impacting the developing human brain, the available methods were primitive, time-consuming, and costly animal tests. Dr. Alan Goldberg, the director of CAAT at the time, decided to concentrate on DNT because there were no formal regulatory requirements to test for such toxicity in animals (the first internationally recognized test guidelines for DNT were approved in 2007 – TG 426 of the OECD). A recent report from CAAT discusses the progress in Developmental Neurotoxicity (DNT) approaches since the first DNT workshop. Although challenging to read, the report is essential for individuals involved in regulatory toxicology. Therefore, no validation of any proposed non-animal DNT methods would be required against an established in vivo approach. Additionally, the available animal tests offered limited comprehension of the fundamental mechanisms of DNT.

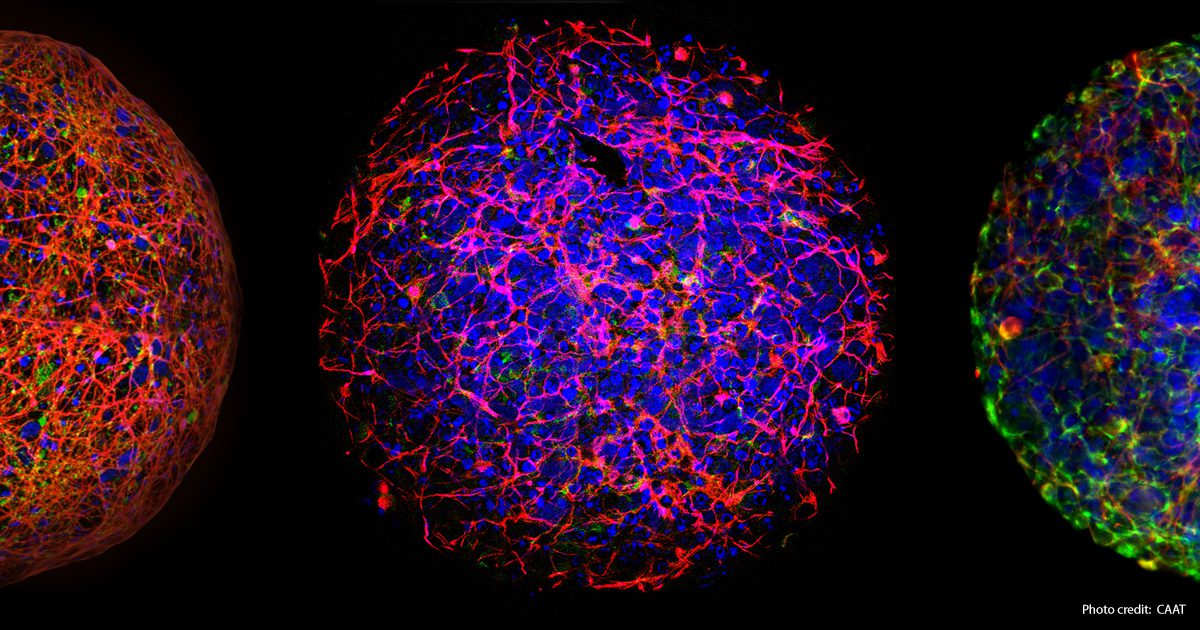

Since the first DNT workshop organized by CAAT 20 years ago, new technologies have been developed using human stem cells to create “mini-brains” – cultured spheres of human nerve cells that mimic many brain cell processes. These technologies enable the exploration of basic mechanisms of nervous system toxicities that may cause cognitive deficits and behavioral abnormalities, such as autism. Dr. Thomas Hartung, the current Director of CAAT, emphasizes that “18 years of collaboration on Developmental Neurotoxicity have shown that animal studies cannot solve the problem, but cell cultures can.” He further mentions that “the next step towards even more relevant models will be human brain organoids.”

On May 20th and 21st, the Interagency Coordinating Committee for the Validation of Alternative Methods (ICCVAM) held a public forum at the National Institutes of Health campus in Bethesda, Maryland. During the forum, there was a presentation about the ComplementARIE project, a new program supported by the NIH Common Fund. This fund was established in 2006 within the Office of the NIH Director to support “time-limited, goal-driven programs that significantly change the trajectory of biomedical research.” The ComplementARIE project recently awarded $1 million in grants to fund twenty projects that advance New Approach Methods.

The ComplementARIE project shares similar goals with national initiatives in the UK, The Netherlands, and Australia, which all encourage the development of New Approach Methods (NAMs) that do not rely on whole animal models. For example, the Netherlands plans to invest 124.5 million euros to transition to animal-free biomedical innovations. This transition is anticipated to provide economic and social benefits through improved medicines and reduced animal testing. Similarly, Australia also recognizes the potential economic and medical benefits of developing NAMs. Their report states, “[T]there is a global trend to reduce reliance on animal models in medical product development.” It predicts a significant increase in the use of advanced non-animal models in all stages of medical product development.

The global trend towards developing and using alternatives to animal testing is illustrated by the creation of non-animal methods to identify substances that can harm brain development over the last 20 years. These new approach methods (NAMs) were anticipated by Sir Peter Medawar, a Nobel Prize Winner in Medicine, in a speech he made in 1969.

In that speech, he emphasized that “The use of animals in laboratories to enlarge our understanding of nature is part of a far wider exploratory process, and one cannot assay its value in isolation – as if it were an activity which, if prohibited, would deprive us only of the material benefits that grow directly out of its own use. Any such prohibition of learning or confinement of the understanding would have widespread and damaging consequences; but this does not imply that we are forevermore, and in increasing numbers, to enlist animals in the scientific service of man. I think that the use of experimental animals on the present scale is a temporary episode in biological and medical history, and that its peak will be reached in ten years’ time, or perhaps even sooner. In the meantime, we must grapple with the paradox that nothing but research on animals will provide us with the knowledge that will make it possible for us, one day, to dispense with the use of them altogether.” 1 (emphasis added)

[1] The Hope of Progress, 1972, Methuen: see also Rowan, Weer & Loew, 1995, pp: 56-57. [Medawar was right when he predicted in 1969 that laboratory animal use would peak in “ten years’ time, or perhaps even sooner.” Laboratory animal use in several developed economies peaked in the mid-1970s. Ed.]