Apr 18, 2025 Giant and Colossal Squid

As a boy, I was fascinated by tales of the Giant squid, *Architeuthus dux*, that inhabit the ocean’s depths. These creatures are challenging to find and observe, and much of what we know about them comes from studies of squid cadavers, body parts recovered from the stomachs of whales and sharks, or dying specimens that wash up on beaches around the world. For instance, the Two Oceans Aquarium in Cape Town, South Africa, reports that at least 60 Giant squid specimens have been found on South African beaches, which accounts for about 9% of all known Giant squid specimens discovered on beaches. Initially, it was thought there were multiple species of Giant squid, but DNA analysis now indicates that the various specimens recovered globally all belong to the same species.

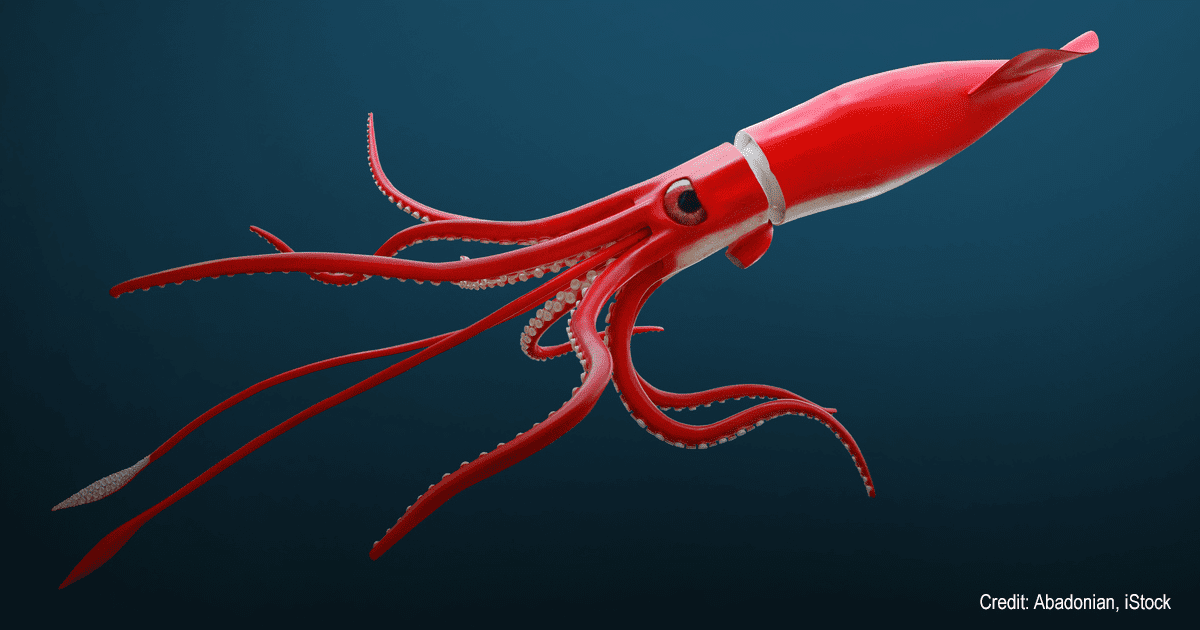

Several other large squid species exist, including a second giant species known as the Colossal squid. The Colossal squid, scientifically named Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni, is much bulkier. It can weigh twice as much as the Giant squid, and its existence wasn’t confirmed until the 1950s. This squid primarily inhabits the depths of the Southern Ocean, in contrast to the Giant squid, which has a global distribution.

In 1981, a Soviet trawler operating off the coast of Antarctica retrieved the first complete specimen of a Colossal squid. This specimen had a mantle length (excluding the head and tentacles) of almost 8 feet and a total length of 17 feet. It was later identified as an immature female.

The evolution of very large squid species is part of a phenomenon known as abyssal giganticism. For instance, spider crabs found at the ocean’s bottom can grow to have a wingspan of 13 feet, while Giant squids can reach lengths of over 40 feet and possibly even longer when their tentacles are fully extended. One explanation for these large sizes is that the deep sea is dark, cold, and has limited food availability. However, as an organism increases in size, its energy requirements relative to its mass decrease. For example, the Greenland shark is a slow-moving Arctic species that can weigh over a ton but needs little food to survive. According to one study, an adult Greenland shark may require as little as 7 ounces of fish or marine mammal prey daily to sustain itself. Additionally, evolving to a considerable size can provide some protection against predation by other ocean creatures.

The Giant squid possesses huge eyes, reportedly the size of dinner plates. The evolutionary pressures that have led to the development of these large eyes may enhance the Giant squid’s ability to detect sperm whales, its primary predator, in the ocean’s dark depths. Giant and Colossal squids have only been filmed on a few occasions. There are three recorded videos of Giant squids, but only two show them in their natural environment. The third video captures a Giant squid brought to the surface after attempting to feed on a lure. There are even fewer videos of the Colossal squid. In 2007, a Discovery Channel video documented a vessel fishing in Antarctic waters that captured a Colossal squid, and there is a preserved specimen of a Colossal squid in New Zealand’s National Museum.

Efforts to film Giant and Colossal squids in the ocean depths have continued, but successful captures have been rare. Recently, a marine expedition managed to capture footage of a Giant squid off the coast of Alabama. The expedition used a camera system called Medusa, which is designed to operate without disturbing the light-sensitive ecosystems in the deep ocean. This system employs a lure that mimics a bioluminescent jellyfish to attract large predators. Notably, a Medusa system previously recorded a Giant squid off the coast of Japan in 2012.

Exploration of the ocean depths is advancing rapidly. Thanks to the development of the unobtrusive Medusa camera system, we can undoubtedly expect more videos of Giant squids. As Fred Aldrich (1927-1991), a marine biologist from Memorial University who studied Giant squids, famously said, “The ocean’s bottom is more interesting than the moon’s surface.”