Dec 07, 2020 Ending Dog Homelessness Across the World

There are many organizations, municipalities and individuals around the world dedicating time, resources and much attention and love to the well-being of dogs and ending dog homelessness. Often, these projects do not have sufficient resources to reach the number of dogs to have measurable impact or they may have short-term success only to find progress is reversed in three or four years, if not sooner. We need data derived from both short- and especially long-term projects, as well as regular reporting of results and appropriate analyses to identify changes that may need to be made to these projects. Usually, the organizations and individuals running these projects do not have the capacity and/or resources to document and store their results. But there are also additional challenges that must be addressed to deal with global dog well-being.

Defining “Homelessness” and Identifying how many Dogs are “Homeless.”

The first challenge is the development of an estimate of the total number of dogs globally and in different countries, and the proportion of dogs in each country who are “homeless.” There have been only a few serious attempts to estimate how many dogs there might be in the world and these estimates range from 400 million to one billion. WBI has been collecting data to produce an estimate of the total global dog population and the proportion that are homeless in different countries. At this point, we are relatively confident that there are approximately 800 million dogs in the world today.

The size of the homeless dog population is trickier to estimate because there has been little discussion of what would constitute a “homeless” dog. Recent research indicates that many dogs that are roaming on the streets may be claimed by a particular household but that does not mean they will receive any veterinary care or regular food. WBI has adopted a definition that considers a dog to be homeless if it spends most or all of its time on the street and receives some food and water from households but very limited or no veterinary care or if it is abandoned by a household who previously cared for it.

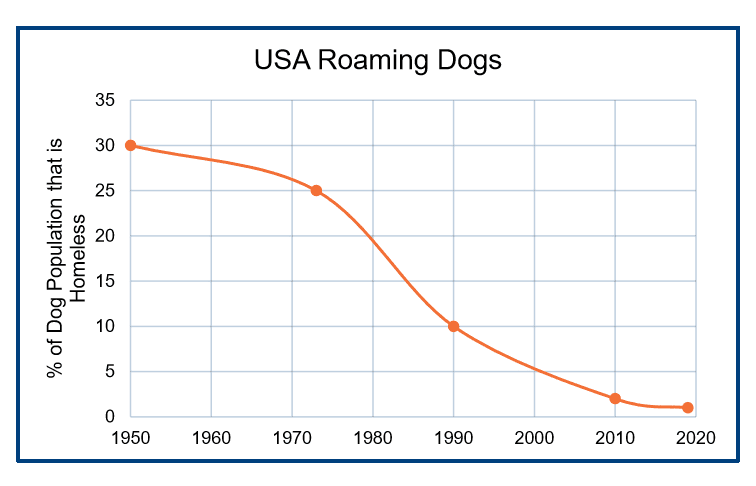

Given the above definition, there are now relatively few “homeless” dogs in High Income Countries. For example, there are probably no homeless dogs in Sweden but somewhere between one and two million homeless dogs in the USA (the total dog population is around 80 million). However, the homeless dog situation in the USA used to be much worse. Just after World War II, around 30% of dogs in the US were “homeless.” In the 1970s, animal groups launched a concerted effort to end dog homelessness in America and the chart to the left (“USA Roaming Dogs”) demonstrates the success of those efforts.

Given the above definition, there are now relatively few “homeless” dogs in High Income Countries. For example, there are probably no homeless dogs in Sweden but somewhere between one and two million homeless dogs in the USA (the total dog population is around 80 million). However, the homeless dog situation in the USA used to be much worse. Just after World War II, around 30% of dogs in the US were “homeless.” In the 1970s, animal groups launched a concerted effort to end dog homelessness in America and the chart to the left (“USA Roaming Dogs”) demonstrates the success of those efforts.

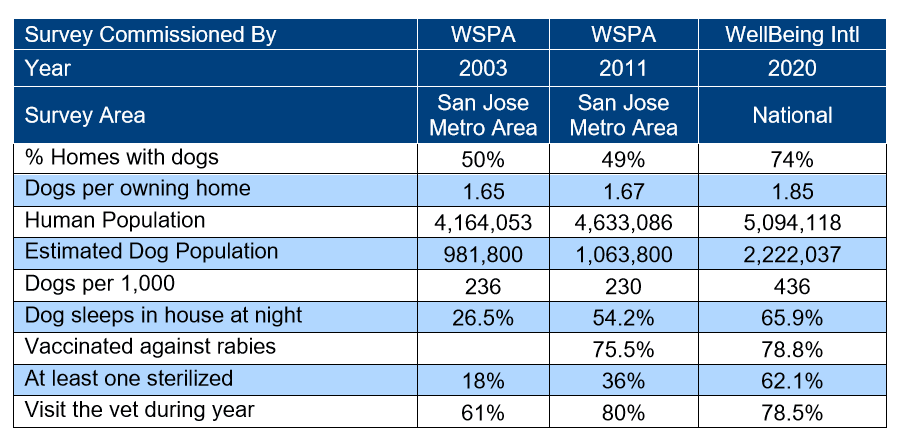

Today, many Latin American countries have a “homeless” dog issue similar to the US at the beginning of the 1970s. But there are signs that this situation is changing, and changing quite rapidly. WBI just completed a dog survey in Costa Rica in which we sought data that would allow us to compare results against those of earlier surveys (in 2003 and 2011). The Costa Rica Survey as shown in the table below provides a snapshot of the changes that are occurring in that country.

As is evident from the data, there has been a substantial change in the human-dog relationship in Costa Rica over the past twenty years. In the US, there was a very big jump in dog sterilization rates from 1970 (under 10%) to 1990 (60% or more) and something similar now appears to be happening in Costa Rica. The vast majority (perhaps 80% or more) of the sterilizations performed in the US from 1970 to 1990 were performed by private veterinary clinics. In Costa Rica, there has been a many-fold increase in the membership of the College of Veterinarians (the official registration organization) since 2000 and there are now twice as many veterinary practices in Costa Rica (around 12 per 100,000 people) as there are in the USA (around 6 per 100,000).

There are indications that the human-dog relationship has also begun changing in Asia while efforts to address homeless dog populations in Africa are growing (mostly based on rabies control projects). A change in small animal veterinary capacity is one possible way to help track changes in human-dog (and human-pet) interactions around the world.

This past week (on Giving Tuesday, 2020), WellBeing International officially launched our Global Dog Campaign. WBI has been developing the infrastructure (mostly virtual) and recruiting the expertise that will be needed to implement what is a very ambitious plan – namely, ending dog “homelessness” across the globe and improving the well-being of both dogs and the communities (including people and the environment) that the dogs inhabit.