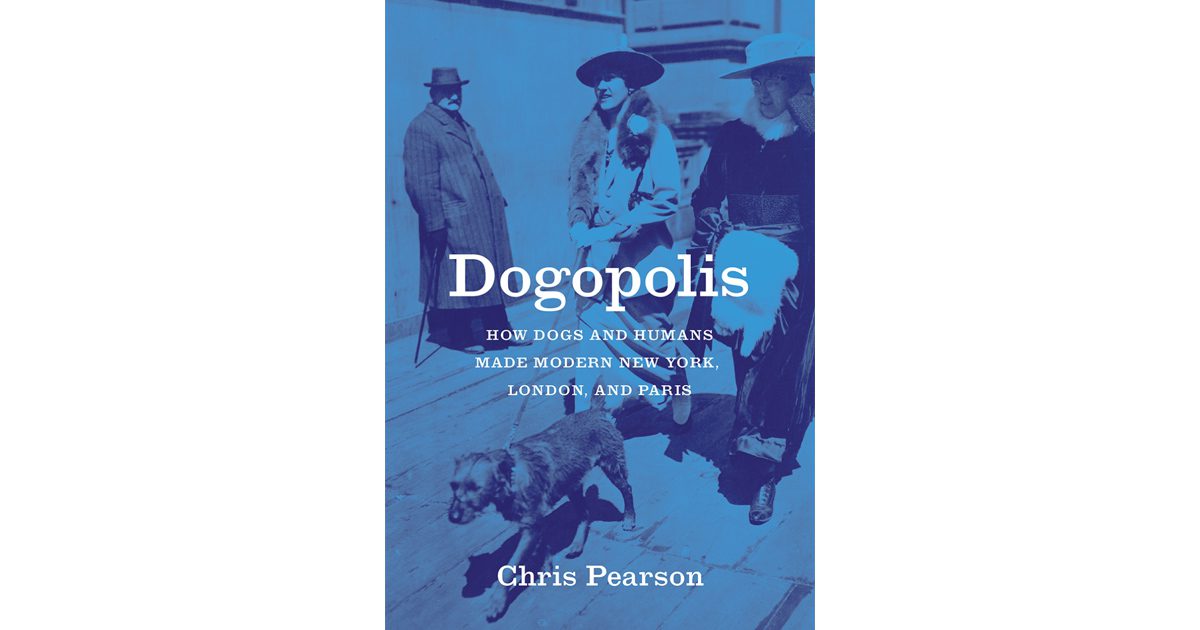

Jun 26, 2023 “Dogopolis: How Dogs and Humans made modern New York, London, and Paris” by Chris Pearson

Book Review

Dr. Chris Pearson, a Senior Lecturer in Twentieth Century History at the University of Liverpool, focuses on animal and environmental history. Dogopolis is his recent book published by the University of Chicago Press that explores the impact of dogs and dog management on primarily the 19th Century development of three major Western cities – Paris, London, and New York.

Readers should start the book by reading the Appendix – Reflections on Animals, History, and Emotions. In this Appendix, Pearson notes the importance of human emotions such as fear, disgust, and compassion in unpacking the impact of dogs and dog management in the development of the three cities and provides context for his analysis of the history of human-dog interactions and how those interactions influenced municipal development.

The book is divided into five main chapters with one-word titles – straying, biting, suffering, thinking, and defecating – covering the 19th century and part of the 20th up to 1939. Anybody involved in modern-day dog management will immediately recognize the topics covered by four chapters but may be stumped by the focus of the chapter on “thinking.” In this chapter, Pearson discusses the development of dogs being trained for use by the police and notes that “supportive middle-class observers placed great faith in these dogs’ thinking abilities” and welcomed their contributions to public safety.

Pearson provides a brief chronology of events by decade from 1810 to 1939 featuring stray dogs and their connections with working-class parts of the three cities and how strays were managed (or not managed) by city agencies. The scourge of rabies, its etiology (some argued rabies was caused by canine sexual frustration), and how it might be eliminated or controlled was a significant issue in all three cities. The muzzling of dogs was one suggested tool that occasioned considerable debate and public conflict. Dealing with stray dogs and developing shelters were common sources of disagreement. Finally, the question of dog “mess” (the euphemism for dog feces) on pedestrian walkways and how best it might be addressed was another source of conflict for the human residents of the three cities.

Pearson’s book is complemented by a doctoral thesis by Frederick L Brown, who described the presence of animals and animal management in Seattle in the 20th century, and by Constance Perin’s Belonging in America: Reading between the Lines (University of Wisconsin Press, 1988). Brown commented on the history of dogs and their management in Seattle and other cities on America’s West Coast and how public pressure to remove dogs from Seattle’s streets in the 1950s resulted in the passage of municipal leash laws that ultimately ended canine strolling in the city where and when desired. The management of the dog movement may have started in London, New York, and Paris. Still, an increase in the control of dog movement in urban areas appears to be a common feature of modern city management. In some countries (e.g., India), roaming dogs is still common in cities. However, in North America and Western Europe, the presence of dogs roaming the streets in the absence of actual or apparent human control is increasingly rare. Perin’s book features a chapter on dogs (“Perfect Dogs”) in urban environments and how people’s attitudes to dogs cemented or disrupted urban communities.

Dogopolis recently added to Dr. Pearson’s work and publications on dog-human relationships. In 2011, he launched a blog, Sniffing the Past, featuring various historical observations and materials on all things canine. It is a treasure trove of reports and observations on dog history, especially in urban centers, and provides additional observations and comments on canine influences on municipal managers.