Jul 08, 2024 Climate, Health and Dengue

Impact of Climate on Human Health

On April 5, 2024, the World Bank released a brief on the impact of climate change on human health. According to the report, a warmer climate could result in at least 21 million additional deaths by 2025 due to five significant health risks: extreme heat, stunting, diarrhea, malaria, and dengue. Two months later, on June 5, 2024, The Lancet published an editorial and a detailed report for World Environment Day on the same topic. The editorial highlighted that the summer of 2022 caused “60,000 heat-related premature deaths in Europe,” with twice as many women affected as men. Food scarcity is another potential threat. The Lancet noted that, in 2021, moderate to severe food insecurity affected almost 12 million people in Europe.

According to The Lancet, despite the 2015 agreement to limit the global temperature increase to 1.5°C, the world’s average temperature was 1.61°C above pre-industrial levels from May 2023 to April 2024. The Lancet report emphasized that “unprecedented warming demands unprecedented action.”

Expanding Dengue Risk

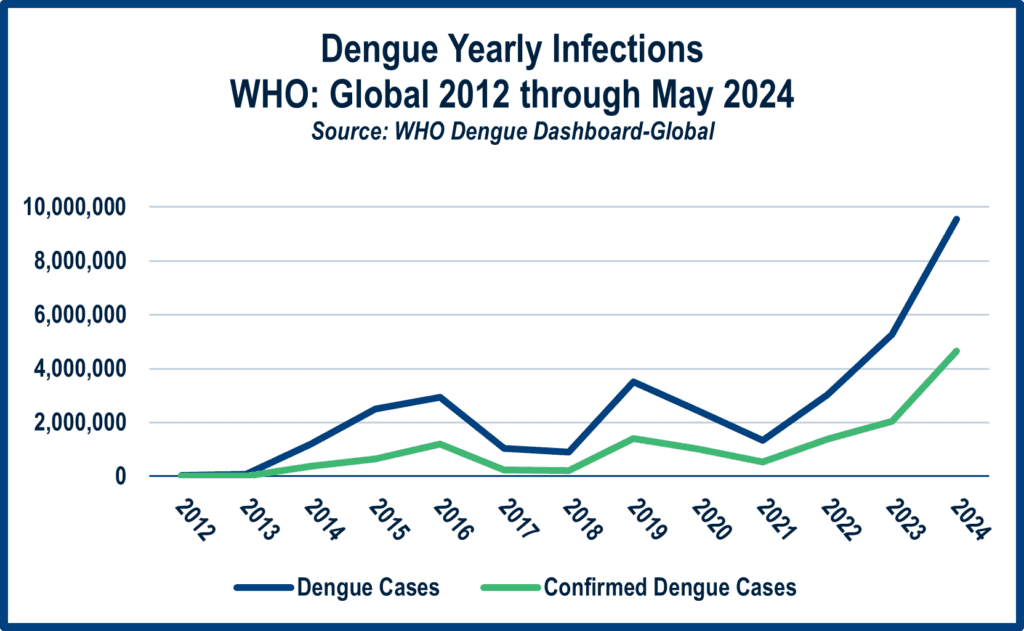

Due to global warming, more regions and countries will be at risk of new vector-borne diseases. For instance, the Aedes aegypti mosquito, which carries dengue, yellow fever, and chikungunya, among other viruses, is expanding its range worldwide, leading to increased dengue fever incidence. Global dengue fever cases fluctuated between 0.9 and 3.5 million from 2017 to 2021 but rose to 3 million in 2022, 5.3 million in 2023 and almost 10 million in the first five months of 2024.[1] Dengue is not the only example of a possible climate-caused increase in disease incidence. West Nile virus, Zika, malaria and leishmaniasis are also expected to increase. At the same time, the ranges of certain tick species, such as the Ixodes deer tick vector transmitting Lyme disease, will also expand.

Due to global warming, more regions and countries will be at risk of new vector-borne diseases. For instance, the Aedes aegypti mosquito, which carries dengue, yellow fever, and chikungunya, among other viruses, is expanding its range worldwide, leading to increased dengue fever incidence. Global dengue fever cases fluctuated between 0.9 and 3.5 million from 2017 to 2021 but rose to 3 million in 2022, 5.3 million in 2023 and almost 10 million in the first five months of 2024.[1] Dengue is not the only example of a possible climate-caused increase in disease incidence. West Nile virus, Zika, malaria and leishmaniasis are also expected to increase. At the same time, the ranges of certain tick species, such as the Ixodes deer tick vector transmitting Lyme disease, will also expand.

Approximately 80% of global dengue fever cases occur in South, Central and North America and the Caribbean[2]. Puerto Rico has been particularly hard hit by dengue in the last few years, and the island may serve as a possible warning of what could be in store for the southern states of the USA. The Centers for Disease Control predict that Aedes aegypti will likely spread further across the Southern US and into California, Midwestern, and Mid-Atlantic states as the country warms up.

Most people infected with Dengue do not have symptoms, but for those who do, the most common symptoms are high fever, headaches, body aches, nausea and rash. For symptomatic cases, treatment usually involves dosing with painkillers. While most cases resolve in one to two weeks, dengue is fatal in a small percentage of symptomatic cases (typically fewer than one case in 1,000).

The virus is expected to spread into new regions in the coming decades, but most of the increased risk of dengue will occur in areas where the virus is already endemic. As temperatures rise, the mosquito vector bites more often, and the dengue virus replicates faster. Higher rainfall produces more pools of water where mosquitoes can lay eggs. People keep doors and windows open during hot weather to cool their homes. Furthermore, as more people become infected with the virus, more mosquitoes will become dengue carriers. Dengue outbreaks tend to occur every three to five years.

Implementation Challenges

The 77th World Health Assembly passed a resolution earlier this year identifying climate change as a major public health threat and urging the development of climate-resilient and sustainable public health systems. This resolution and reports by the World Bank and the Lancet signify a growing political commitment to include climate action as a public health priority. However, implementing effective new policies remains a challenge. Furthermore, the necessary economic shifts, including the cost of implementing new policies and timelines that may be overly optimistic, generate understandable tensions in many countries while reaching a new political consensus among public and private stakeholders. Finally, implementing the agreed-upon climate targets is “where the rubber meets the road.”

For example, fossil fuel subsidies in the European Union (EU) are increasing even though Europe’s Eighth Environment Action initiative called for an immediate phase-out of such subsidies. In November 2023, the European Environment Agency (EEA)[3] reported that European Union members subsidized fossil fuels to around 50-60 billion euros per year from 2015 to 2021. Those subsidies increased to 123 billion euros in 2022. The EEA explained that energy prices increased during the post-pandemic recovery and after Russia invaded Ukraine. It also noted that Europe plans to end around 58 billion euros of fuel subsidies by 2025. However, that would leave approximately 60 billion euros of fuel subsidies in place. The extended European timeline to eliminate fossil fuel subsidies reflects the political, economic, and logistical complexity of implementing effective climate change measures.

More Buzz on The “Hateful” Mosquito

More Buzz on The “Hateful” Mosquito

The mosquito, Aedes aegypti, has a well-deserved status as a pest (its genus name is derived from the Greek for “hateful”). The mosquito also has a complicated evolutionary history. Powell and his colleagues summarize the mosquito’s evolution from a wild to a “domesticated” species as it changed from preferring natural water pools in forests and the blood of animals (labeled form aaf) to laying its eggs in water stored by humans and sipping on human blood (form aaa). Tracking the history of aaf and aaa is challenging. Different people used different names for the same mosquito (medical teams in Cuba investigating yellow fever outbreaks called the mosquito vector Culex fasciata, but Powell et al. state there is little doubt the mosquito spreading the disease was Aedes aegypti). The advent of modern DNA technologies and the historical evidence of specific disease outbreaks (e.g., yellow fever and dengue) transmitted by the mosquito allows the construction of a history of the domestication of Aedes aegypti and its global spread out of Africa.

Approximately 500 years ago, Aedes aegypti spread from West Africa to the New World via the slave trade. The first reliable report of a yellow fever outbreak in the New World occurred in 1648 in Havana. Like the mosquito, yellow fever came from Africa. The virus remains infective in human carriers for only 7-10 days, while adult mosquitoes seldom live longer than a month. The slave ships took 2-4 months to travel from Africa to the New World. Therefore, there must have been active reinfections of humans with the yellow fever virus by mosquitoes surviving and breeding in the ships. The mosquito and its viral diseases then spread to Asia around 200 years ago.

Video credit: Melissa Harp, Shutterstock

[1] Dengue and severe dengue (who.int), Dengue- Global situation (who.int).

[2] WHO ‘Region of Americas’ includes the following countries: Antigua and Barbuda, Argentina, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Curaçao, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, French Guiana, Grenada, Guadeloupe, Guatemala, Guyana, Honduras’ Jamaica, Martinique, Mexico, Montserrat, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Puerto Rico, Saint Barthélemy, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Martin (French part), Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Sint Maarten (Dutch part), Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago, Turks and Caicos Islands, United States Virgin Islands, United States of America, and Uruguay.

[3] European Environment Agency published report, November 17, 2023. Fossil fuel subsidies | European Environment Agency’s home page (europa.eu).