Aug 17, 2021 Cat Management Successes

Over the past five to ten years, the academic literature on cat management (specifically outdoor cat management) projects have been enriched by dozens of papers looking at public attitudes to cats and different cat management options and detailing the effects of some cat management projects in different parts of the world. Nevertheless, the controversy over what to do about cats continues unabated, it seems. One of WBI’s Global Ambassadors (Dr. John Hadidian) has just completed an extensive review of cat management. His review, looking at the history of the issue from an animal welfare perspective, hopes to provide a starting point for anybody who wishes to explore cat management in depth. Readers can find his review in the WellBeing International Studies Repository. But there have been several cat management projects whose results are not available in the scientific literature. We want to describe four of them in this newsletter.

San Nicolas Island Cat Management. San Nicolas Island (area of 59 Km2) is a remote member of the Channel Islands off the coast of California. The US Navy manages the island and recently decided to do something about a population of feral cats preying on island wildlife and competing with the endangered island fox. Cats were brought to the island in the 1950s by Navy personnel but then went feral. The concerns about the impact of these cats on the island’s wildlife led to a plan to trap and remove them. A funder provided $3 million to support the project, and trapping of the cats began in 2008. By 2010, a total of 66 cats had been caught and removed from the island. The Humane Society of the United States agreed to find homes for the cats or permanently house the remaining cats at one of its wildlife centers. While the project successfully removed all the cats from the island, the ultimate cost of removal and subsequent housing has cost approximately $60,000 per cat. The expense is an obvious downside to the project, but the real point of the effort and the real upside was the rare collaboration among conservation and animal protection interests.

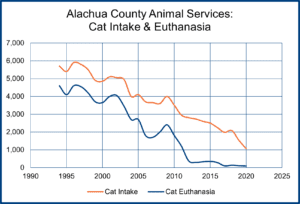

Alachua County, Florida. In the mid-1990s, Dr. Julie Levy, a member of the University of Florida veterinary school faculty, started an outdoor-cat trapping and sterilization project in Alachua County. Outdoor cats were ubiquitous throughout the county and may have amounted to 40% of the total cat population. Since the program’s beginning, Dr. Levy, her colleagues, and students have sterilized approximately 65,000 cats (averaging around 2,500 a year but in recent years they have averaged 5-6,000 sterilizations a year). The graph indicates how cat intake and euthanasia numbers at Alachua County Animal Services, the dominant shelter facility in the county, have fallen since her project began. Cat intake by the facility has dropped by a factor of six, and cat euthanasia has declined by around 98%. Wildlife conservation advocates have argued that one cannot draw inferences about outdoor cat populations from animal shelter intake and euthanasia numbers. Strictly speaking, they are correct. But it is certainly possible to use the shelter intake and euthanasia numbers to infer that the outdoor cat situation in Alachua county is better (much better?) today than it was in 1994.

Alachua County, Florida. In the mid-1990s, Dr. Julie Levy, a member of the University of Florida veterinary school faculty, started an outdoor-cat trapping and sterilization project in Alachua County. Outdoor cats were ubiquitous throughout the county and may have amounted to 40% of the total cat population. Since the program’s beginning, Dr. Levy, her colleagues, and students have sterilized approximately 65,000 cats (averaging around 2,500 a year but in recent years they have averaged 5-6,000 sterilizations a year). The graph indicates how cat intake and euthanasia numbers at Alachua County Animal Services, the dominant shelter facility in the county, have fallen since her project began. Cat intake by the facility has dropped by a factor of six, and cat euthanasia has declined by around 98%. Wildlife conservation advocates have argued that one cannot draw inferences about outdoor cat populations from animal shelter intake and euthanasia numbers. Strictly speaking, they are correct. But it is certainly possible to use the shelter intake and euthanasia numbers to infer that the outdoor cat situation in Alachua county is better (much better?) today than it was in 1994.

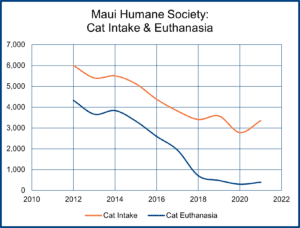

Maui Island, Hawaii. Following a conference on the outdoor cat issue, organized in 2012 with the support of the Found Animals Foundation, both of us began to explore the potential to develop an effective cat management project on Maui in Hawaii. This exploratory project was prompted by one speaker’s suggestion at the conference that the island of Maui (around 1,800 square kilometers and a human population of 150,000) may be home to as many as 500,000 outdoor cats. We both visited Maui to identify people engaged in cat management and to determine what might be done if anything. Following the visit, we commissioned a census of outdoor cats in two of Maui’s conservation hotspots. The census identified around 3,000 outdoor cats in and around the main town on the island, from which we estimated that the actual population of outdoor cats might be 30-40,000. Maui Humane Society, the main shelter on the island, received grants from several foundations to support a new, comprehensive cat management program that became fully operational towards the end of 2014. The impact of this approach on cat intake and euthanasia by Maui Humane Society is shown in the graph.

Maui Island, Hawaii. Following a conference on the outdoor cat issue, organized in 2012 with the support of the Found Animals Foundation, both of us began to explore the potential to develop an effective cat management project on Maui in Hawaii. This exploratory project was prompted by one speaker’s suggestion at the conference that the island of Maui (around 1,800 square kilometers and a human population of 150,000) may be home to as many as 500,000 outdoor cats. We both visited Maui to identify people engaged in cat management and to determine what might be done if anything. Following the visit, we commissioned a census of outdoor cats in two of Maui’s conservation hotspots. The census identified around 3,000 outdoor cats in and around the main town on the island, from which we estimated that the actual population of outdoor cats might be 30-40,000. Maui Humane Society, the main shelter on the island, received grants from several foundations to support a new, comprehensive cat management program that became fully operational towards the end of 2014. The impact of this approach on cat intake and euthanasia by Maui Humane Society is shown in the graph.

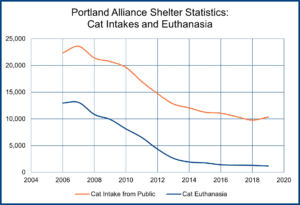

Portland, Oregon Cat Management. Another rare collaboration between a wildlife conservation group (Portland Audubon) and an animal protection group (Feral Cat Coalition of Oregon) has blossomed in Portland over the last twenty years. Both organizations agreed to work together based on an agreement to protect both birds and cats (rather than emphasizing birds versus cats) and the recognition that is caring for cats and birds are not mutually exclusive. The two organizations also focused on long-term solutions rather than on symptoms and emphasized tracking statistical trends. Portland now has a thriving “catio” scene where cat owners build outdoor catios that allow their pets outdoor access without access to wild animals. The Feral Cat Coalition organizes trendy tours of sample catios. Portland Audubon is investigating cat demographics on Hayden Island. The island has roughly one-half of a semi-wild area, while human homes and apartments make up the rest. The initial reports indicate that the outdoor cats mainly stay around human residences, are rarely found in the wild areas, and two-thirds of what they eat is commercial cat food. Meanwhile, cat intake and euthanasia in the shelters in the four counties that comprise the Animal Shelter Alliance of Portland have plummeted (see chart).

Portland, Oregon Cat Management. Another rare collaboration between a wildlife conservation group (Portland Audubon) and an animal protection group (Feral Cat Coalition of Oregon) has blossomed in Portland over the last twenty years. Both organizations agreed to work together based on an agreement to protect both birds and cats (rather than emphasizing birds versus cats) and the recognition that is caring for cats and birds are not mutually exclusive. The two organizations also focused on long-term solutions rather than on symptoms and emphasized tracking statistical trends. Portland now has a thriving “catio” scene where cat owners build outdoor catios that allow their pets outdoor access without access to wild animals. The Feral Cat Coalition organizes trendy tours of sample catios. Portland Audubon is investigating cat demographics on Hayden Island. The island has roughly one-half of a semi-wild area, while human homes and apartments make up the rest. The initial reports indicate that the outdoor cats mainly stay around human residences, are rarely found in the wild areas, and two-thirds of what they eat is commercial cat food. Meanwhile, cat intake and euthanasia in the shelters in the four counties that comprise the Animal Shelter Alliance of Portland have plummeted (see chart).

What do these case studies tell us? One take-home is that conservation and animal advocates can work together to address what some feel is an irresolvable conflict over outdoor cats. Three of the four examples above – Alachua, Portland & San Nicolas – have involved engagement between wildlife and cat advocates. This collaboration does require trust, but we need to remember that both have the same fundamental interest at heart – fewer cats outdoors, with less risk to cats and less threat to wildlife. Another take-home is that “solving” the issue of outdoor cats will not be easy, nor will it happen overnight. Every situation involving cats will be unique, with solutions that need to be tailored to many factors and individual circumstances. But as these different cases show, we can move the needle on this issue and, most importantly, do it humanely.