May 20, 2024 “Branching Out: Examining Plant Cognition and Sentience”

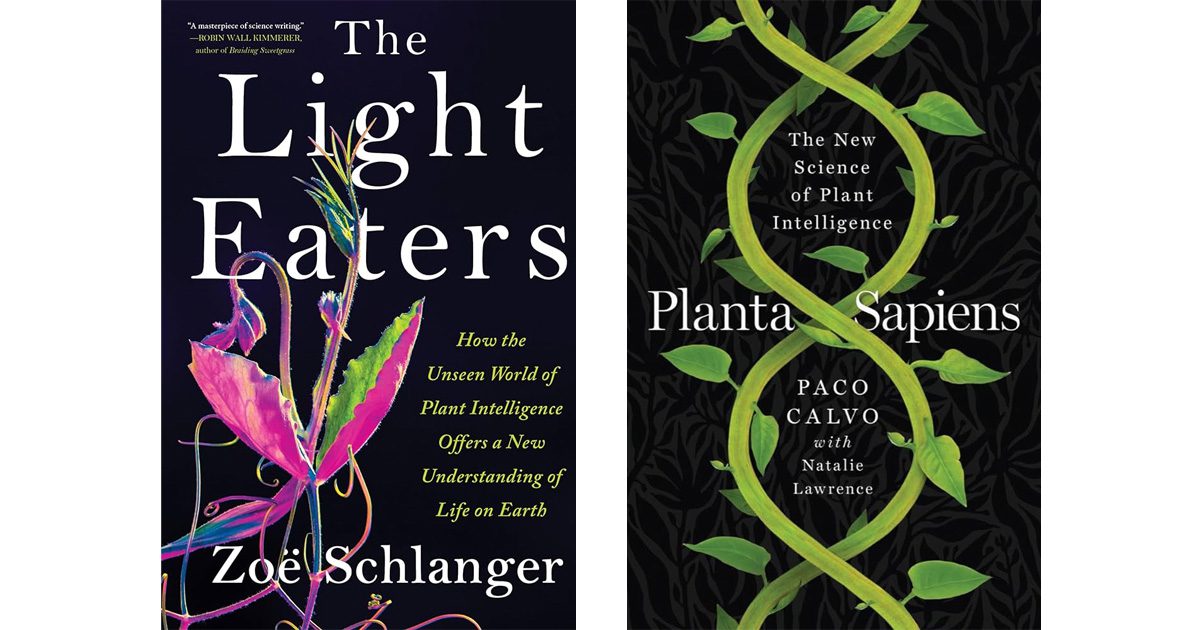

The Light Eaters by Zoe Schlanger & Planta Sapiens by Paco Calvo with Natalie Lawrence

Recently, two important books were published — a year apart – and centered on the same topic: reviewing the accumulating scientific evidence that plants can and should be perceived as sentient and also as intelligent, as demonstrated by their abilities to process information, communicate it, adapt to it, protect family members, remember, and pass their memories on to others.

A staff writer for the Atlantic Monthly, Zoe Schlanger wrote “The Light Eaters – How the Unseen World of Plant Intelligence Offers a New Understanding of Life on Earth” (HarperCollins), which links the case for greater respect for plants to how science changes paradigms, and scientists change their minds about settled wisdom from one time period to another, quoting Thomas Kuhn’s influential work on the non-linear paradigm shifts in scientific beliefs. Schlanger comes to the topic as a curious outsider. “The more botanists uncovered the complexity of forms and behaviors of plants, the less the traditional assumptions about plant life seemed to apply.” She organizes her book around milestones and advances in the history of botany, including long views of ancient ferns and slime molds, and the migration from aquatic plants to plant land colonization 500 million years ago. Colonizing all seven continents was challenging, but she comments: “To survive, reproduce and establish complex communities – all while thwarting the pressures of predators, seasons, scarcity and blight—was another thing entirely.”

The other book, “Planta Sapiens: The New Science of Plant Intelligence” authored by Paco Calvo with Natalie Lawrence, was also released in 2023. The subject is closer to Calvo’s professional career, as he heads a research laboratory in Spain, the Minimal Intelligence Lab, dedicated to the issues covered in the book. An article by Segundo-Ortin and Calvo arguing that plants are sentient was recently published in the Animal Sentience journal by WellBeing International. In Planta Sapiens, Calvo and Lawrence also argue that plants exhibit behaviors that suggest cognitive capacities, such as learning from experience, remembering past stressors, and making decisions based on environmental cues. Plant intelligence is defined as the ability of plants to learn from experience, remember past events, and make decisions based on environmental cues.

Reviewers are very positive about both books. Laura Miller wrote in Slate (May 4, 2024): “The Light Eaters is one of those science books in which the author travels to richly described locales to interview assorted researchers at work and to vividly describe their discoveries for a general audience. (Ed Yong’s An Immense World, about the sensory universe of animals, is the best-known recent example.)”

In the New York Times (June 23, 2023), Temple Grandin (who has written extensively on animal welfare and animal cognition) reviews the Calvo and Lawrence book and concludes that “the book does contain evidence that some plants have structures that can certainly function like simple nervous systems. These are very different from neurons, but they can perform some of the same tasks.”

Both books challenge conventional scientific assumptions and biases about what sentience must look like, and both make the case that having a brain is an insufficient criterion for acknowledging intelligence and sentience. The two books hold that those who argue against plant intelligence invoke circular animal-centric reasoning, which is at odds with recent research into animal sentience. Schlanger observes how animals (like dogs) were, until recently, viewed as having no intelligence or soul or being “worthy of some semblance of humane treatment.”

Schlanger frames her story around key research findings that overturn common views of plants. She also cautions that the topic was set back by the popularity of the 1973 book The Secret Life of Plants, written by Peter Tompkins and Christopher Bird. The book promoted many myths that botanists have been refuting ever since.

The notion that plants can cleverly retaliate against animals was mainstreamed in the popular M. Night Shyamalan 2008 feature movie “The Happening”, in which trees collaborate in releasing neurotoxins that lead much of humanity to commit suicide. Though this has not yet happened, plants actually do something similar in their response to their main predator, caterpillars. (note by reviewers)

A wide range of plants can distinguish themselves from others and can tell if they are related, leading to plants re-arranging their leaves to avoid shading next of kin. Trees communicate with other trees via their roots and various chemical signals. If communication is a vital function of plants, then our care for them must also protect their ability to “talk” to one another. “Indeed, the relationships plants have with other plant species, and even with animals, is a tapestry of dynamics that run the gamut from reciprocal to exquisitely antagonistic.”

Some plants are highly sensitive to touch, remember contact patterns, and adapt to specific experiences daily. “Glutamate and glycine, two of the most common neurotransmitters in animal brains, are present in plants also, and seem to be crucial to how they pass information through their stems and leaves. They have been found to form, store, and access memories, sense incredibly subtle changes in their environment, and send highly sophisticated chemicals aloft on the air in response. They send signals to different body parts to coordinate defenses.” [Glutamate and Glycine are two of the twenty standard building blocks for all proteins, whether plant or animal, and are found in all living systems. Both molecules are also neurotransmitters in vertebrate nervous systems. Ed]

Calvo, a philosopher and biologist, is more of an insider and suggests that recognizing plant intelligence could lead to a more profound understanding of the natural world and potentially aid in addressing environmental challenges. Planta Sapiens uses scientific research to spur philosophical debate about why plants should be considered intelligent. For example, the book describes how plants’ physiological processes, including electrical signaling in plant vascular systems, are similar to animal nervous systems.

Calvo provides many examples of adaptive plant “behavior”: Flowers can time their pollen production to coincide with pollinator visits, indicating a form of memory and anticipation. Even within a given species, habitat and place, individual plants exhibit different “personalities,” with each plant showing distinctive preferences and behaviors. Like Schlanger, he explains how plants perceive their environment through chemical signals and detect and respond to various chemical stimuli, including those indicating water, nutrients, and the presence of other plants or pathogens. Plant hormones like auxin, cytokinin, gibberellin, abscisic acid, and ethylene play crucial roles in mediating these responses, affecting many aspects of plant life from flowering to defense mechanisms against stress.

Planta Sapiens raises ethical questions about how we treat plants, suggesting that if plants are indeed intelligent, they might deserve considerations similar to those we increasingly extend to animals. Calvo and Lawrence suggest that a deeper understanding of plant intelligence could advance robotics and artificial intelligence developments. They also raise the issue of whether there should be campaigns for plant rights.

Steven Hansch is a humanitarian aid specialist with extensive field, management, and evaluation experience. He teaches at several universities and serves on several nonprofit boards involved in human development and humanitarian aid. Leslie Barcus has served on national and international animal protection organization boards. Her professional activities include work in more than forty countries addressing animal protection, microfinance, biodiversity conservation, organizational capacity building, and international economic development.