Dec 16, 2021 “Avian Illuminations” By Boria Sax

In the early days of Anthrozoos, the first academic journal to focus on human-animal interactions, I met many remarkable individuals who agreed to speak at a series of seminars organized by the Tufts Center for Animals and Public Policy. Perhaps the most successful seminar was one that combined the biology (bald eagle recovery), art (examples from Worcester Art Museum’s collection), and ethnography (human fascination with birds) of birds. At first, the seminar’s success was a surprise, but after reflection, I concluded that humans and birds had been deeply connected for millennia.

To realize this connection, one only has to look at the fascination of bird watching. My mother became a professional ornithologist but only after decades of bird watching. Today, bird feeders are ubiquitous across the USA (around 40% of households) and in the UK (estimates range from 50-75% of households feed birds) and there is a group of bird watchers (or twitchers) who go to great lengths to build life lists of bird species they have seen. There is even a movie about twitchers – The Big Year (well worth 102 minutes of your life) – in which Steve Martin, Owen Wilson, and Jack Black compete to see the most different species of birds in a single year. The record is now 840 species set by John Weigel of Australia in 2019.

But back to Boria Sax’s latest book – Avian Illuminations. Sax was also a featured author in the first ten volumes of Anthrozoos and has long been fascinated by folklore about human-animal interactions (e.g., see his books The Frog King and The Parliament of Animals). He has authored two books for the remarkable Reaktion series on animals (now over one hundred volumes strong). His book on the crow is one of their best sellers. The books in the animal series all have single-word titles and tend to provide short and delightfully idiosyncratic approaches to the title animal. Avian Illuminations is not part of the Reaktion Animal series. It is not brief (coming in at 416 pages), but it certainly exemplifies Sax’s extensive reading and knowledge of the subject.

The book examines birds’ many roles in human society, myth-making and folklore. It is organized into four sections – birds in philosophy and religion, birds in history, birds in art, and birds and the future. Every section contains a mix of avian natural history and examples of birds in human folklore and myth taken from Sax’s encyclopedic knowledge of the ethnography and symbolism of avian characters over four millennia and more of human history. The book can be read from cover to cover or reward a reader who decides to dip into different sections at random.

In one section, Sax discusses the place of the wren in the avian hierarchy and the various tales in which the wren, a tiny bird, vies to be the most unlikely king of the birds. In general, the wren tends to be revered by people across its Eurasian range for 364 days of the year. But, on St Stephen’s Day (the day after Christmas), there may be a wren hunt. This ceremony, in which the little creature is hunted, killed, and then displayed in the community, is an ancient and widespread practice at one time, according to Sax. However, because of modern sensibilities, a wren hunt nowadays does not usually involve a wren’s actual capture and death. Many theories speculate on why people began hunting-the-wren ceremonies.

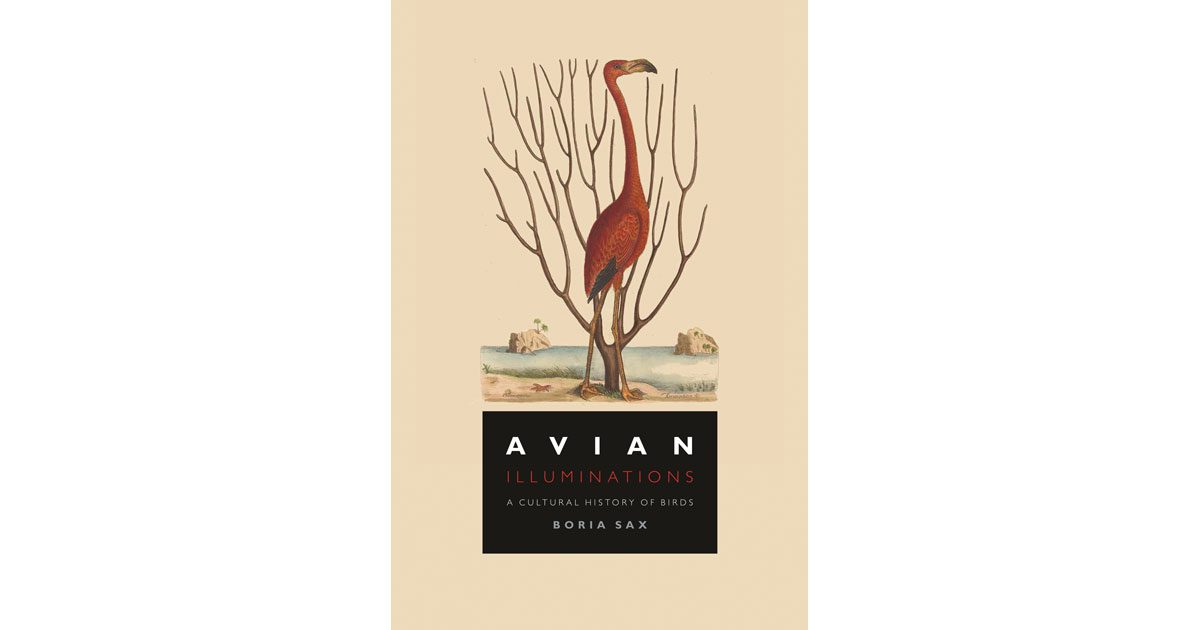

The book is full of gorgeous illustrations of birds in art and avian symbolism. My particular favorite (apart from the elegant flamingo on the cover) was an 1878 woodblock print by Utagawa Hiroshige of “Dancing Swallows” featuring a single swallow facing a conga line of seven companions. It is a whimsical image that, despite its fantastical posing of the birds, somehow captures the elegance and essential characteristics of swallows in flight.

This book would be a marvelous gift for a birdwatcher or budding ornithologist in your home.