Jan 29, 2021 Animal Relinquishment and Pet-owner Resilience

In 2021, it is hoped that the world will slowly return to normal as an increasing proportion of national populations are vaccinated. Such a return will likely mean fewer people working from home and more pets spending their days with less human companionship. Animal groups are concerned that people who have obtained new pets may surrender them to shelters when social distancing measures are relaxed and, perhaps, when moratoriums on foreclosures due to arrears in rent and mortgage are lifted. However, a recent study of pet ownership in a low-income community and an examination of pet surrender in previous financial turndowns indicate that the human-animal bond may be more resilient than animal advocates fear.

This resilience is on full display in Underdogs, a new book describing the challenges faced by people and their pets in low-income communities. Fortunately, as sheltering resources have grown in the US over the past forty to fifty years (tripling and quadrupling in inflation-adjusted dollars), there are now many more programs helping pet owners in low-income communities to manage pet care costs. And yet the research found that simply making free pet food and low-cost veterinary care available are not sufficient to support the human-animal bond in these communities.

This resilience is on full display in Underdogs, a new book describing the challenges faced by people and their pets in low-income communities. Fortunately, as sheltering resources have grown in the US over the past forty to fifty years (tripling and quadrupling in inflation-adjusted dollars), there are now many more programs helping pet owners in low-income communities to manage pet care costs. And yet the research found that simply making free pet food and low-cost veterinary care available are not sufficient to support the human-animal bond in these communities.

Beyond cost and access, the book reports a number of other obstacles to disseminating affordable basic veterinary care. In the most underserved part of Charlotte, North Carolina, some people distrusted the shelter because its sterilization program reminded them of the state’s forced sterilization of young black women (still occurring as recently as 1974). Others felt ashamed or even stigmatized to accept free services. And yet others were afraid that law enforcement or the immigration authorities would track them down through the personal information they gave to the shelter.

The Charlotte Humane Society tried to overcome these barriers so more animals would receive basic veterinary care. Shelter workers reduced their expectations of what underserved communities can reasonably do for dogs and cats, given the realities of living in or near poverty and the constraints of local culture. Elements of “responsible guardianship,” often touted as the gold standard for pet owner behavior, were frequently impossible to achieve and risked further alienating communities that have long distrusted shelters. Therefore, rather than prohibiting or discouraging pet ownership in underserved communities, shelter workers aimed to develop “reasonable” guardianship standards. Shelter workers also tried to improve low-income pet owners’ relationships with their animals as well as with the shelter itself. Such measures included building backyard fences that enabled unruly dogs to become more approachable, in turn making it easier for owners to touch or play with their pets. Shelter workers also cultured special relationships with “community ambassadors” knowing that people who had used the shelter’s affordable care and spoke highly of it would encourage neighbors with pets to also use these services.

To provide basic veterinary care, many people in low-income communities improvised ways to be responsible for their pets, given available resources and support. Examples of such care were common and flew in the face of the negative stereotypes that tend to identify people in low-income communities as irresponsible or neglectful. With fewer resources, some pet owners made significant sacrifices for the sake of their animals’ welfare just as they routinely did for other family members when they were in need.

One pet owner spent his entire Social Security check to pay his sick dog’s veterinary bill even though he had almost no savings to fall back on for personal expenses. Another paid for pet food with money earmarked for baby food. When evictions or financial hardship hit, people found others to take care of their pets, whether temporarily or permanently, instead of abandoning them on the street or to animal control. In one case, a pet owner moved into public housing that required him to give up his dog. He then asked a friend nearby to keep and feed the dog. He would bike over once a week to clean up after his dog and perhaps provide food as well. After the “substitute” owner was evicted from his home because of gentrification, he found another home to keep his dog.

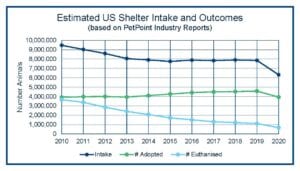

Given that pet-ownership in these low-income communities is much more resilient than commonly assumed, what might we expect of the broader population as the US gradually returns to a more normal society? We would argue that reports of increased interest in pets, influenced by the changing habits of people spending most of their time at home, may not have led to a big increase in overall pet ownership. For example, the gross number of dogs and cats adopted from shelters actually did not increase in 2020. Therefore, there may not actually have been an unusual increase in the number of pets entering US homes in 2020.

Another concern is that economic downturns result in greater relinquishment of pets. Again, there is no evidence of a surge of pet relinquishments during an economic downturn. Pet ownership and expenditures on pets appears to be relatively resistant to economic conditions although there was a dip in veterinary expenditures in 2010 after the last economic downturn.