Nov 13, 2024 Animals in Conflict – Part 1: Conscripts and Victims

This article is the first installment of a three-part newsletter series examining the impact of human conflicts on animals. The newsletter series is adapted from the original blog by Cox and Zee, which was published by the Conflict and Environment Observatory and republished with their kind permission. The citation and link to the original blog are as follows: Cox, Janice & Zee, Jackson, 2021, How animals are harmed by armed conflicts and military activities. March 18. https://ceobs.org/how-animals-are-harmed-by-armed-conflicts-and-military-activities/. The authors updated the article from the original blog in October 2024. Additional comments, with the authors’ approval, by Dr. Andrew N. Rowan have been added in italics.

Introduction

Wild and domesticated animals have long suffered abuse, injury or death in armed conflicts. In this paper, Janice Cox and Jackson Zee explore this history of harm and the reasons behind it, arguing that the animal victims of war require greater recognition and protection.

Animals Conscripted into War Effort

Wild and domesticated animals have long suffered abuse, injury or death in armed conflicts. In this paper, Janice Cox and Jackson Zee explore this history of harm and the reasons behind it, arguing that the animal victims of war require greater recognition and protection.

Before the mechanisation of warfare, armies often conscripted large numbers of animals into service to support their war efforts. Horses, donkeys, oxen, bullocks and elephants carried men, material and supplies; pigeons carried messages; camel-mounted troops were employed in desert campaigns; and cavalry horses often led the charge on the front line.

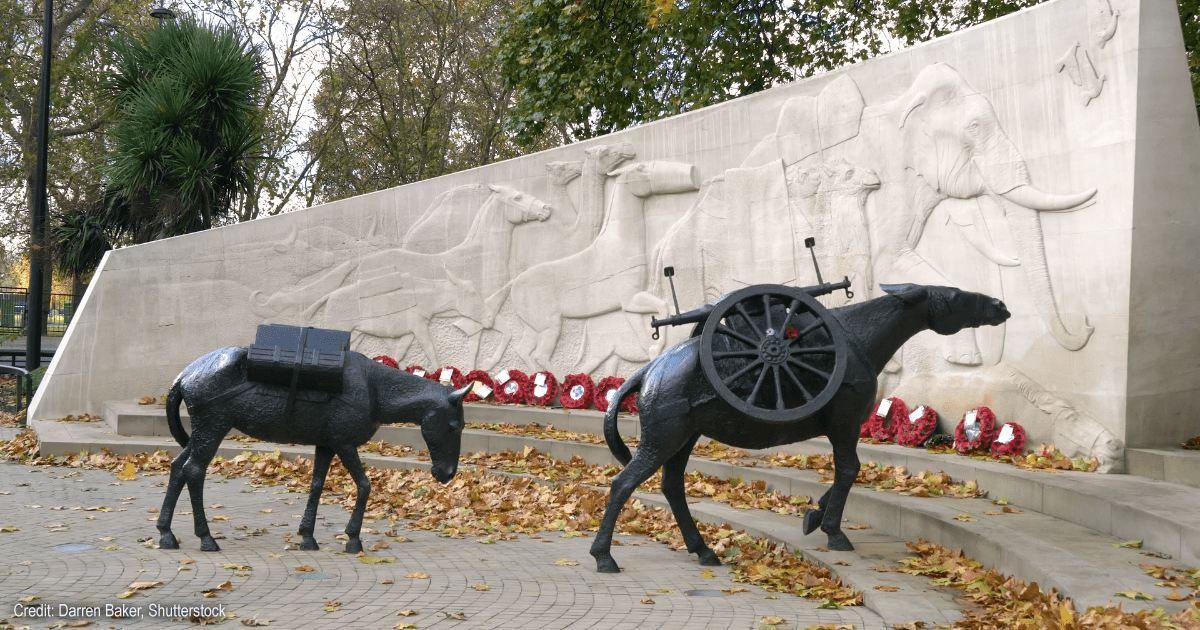

A Guardian article reports that 16 million animals “served” in the First World War, the first industrialized conflict where vast numbers of animals were still in use. The RSPCA has estimated that 484,143 horses, mules, camels and bullocks were killed in British service alone between 1914-18. [ANR comment2 – Maria Dickin, the founder of the People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals in the UK, instituted the PDSA Dickin Medal in 1943 to honor the contributions of animals in World War II. The award is commonly referred to as the animal’s Victoria Cross. The first recipients of the Dickin Medal were three homing pigeons who contributed to the recovery of aircrews from aircraft that had crashlanded in the ocean. In 2004, Princess Anne unveiled a memorial in Hyde Park, London, to the animals who have served and died alongside British and allied troops. Special tribute is given to the 60 animals awarded the Dickin medal, including 32 pigeons, 18 dogs, three horses and a cat.] While the number of animals conscripted to directly support fighting has decreased, their use by militaries remains common.

Dogs have been particularly widely used by the military and remain so today. Their roles include tracking, guarding, delivering messages, laying telegraph wires, detecting explosives and digging out bomb victims. Rats have also been used to detect mines, while dolphins and sea lions continue to be trained to protect harbours from underwater mines and enemy divers. There are reports of cats being used to hunt rats in trenches, canaries being used to detect poisonous gas, and, in World War I, glow worms being used for illumination at night to read communiques and maps.

These activities have often led to animal casualties and deaths, and the shocking death toll is covered in a later article. But there were also untold deprivations and animal welfare issues, ranging from poor training methods, housing, overwork and exhaustion, exposure to heat or cold, starvation, thirst, disease, and abandonment.

Animals have also been widely used in military research, particularly into weapons and injuries. Weapons have been tested for safety and efficacy, usually using pigs and sheep – many of which were shot and killed in testing. Rodents, rabbits, and primates have also been used widely in laboratory testing in relation to the toxicity of weapon constituents, while still more animals have been used to test chemical, biological or radiological warfare or for medical personnel to experiment on and train to deal with burns, blasts and wounds.

[ANR Comment2 – For example, the primate equilibrium platform (PEP) was used to test the ability of primates to keep a platform level after exposure to either toxic agents or ionizing radiation. The PEP was featured in the 1987 film Project X, starring Matthew Broderick and Helen Hunt.

While animals continue to be used in military laboratories, the US Department of Defence commissioned a 2022 report to assess how NAMS (non-animal methods) could be deployed to investigate biomedical issues of interest to the military.]

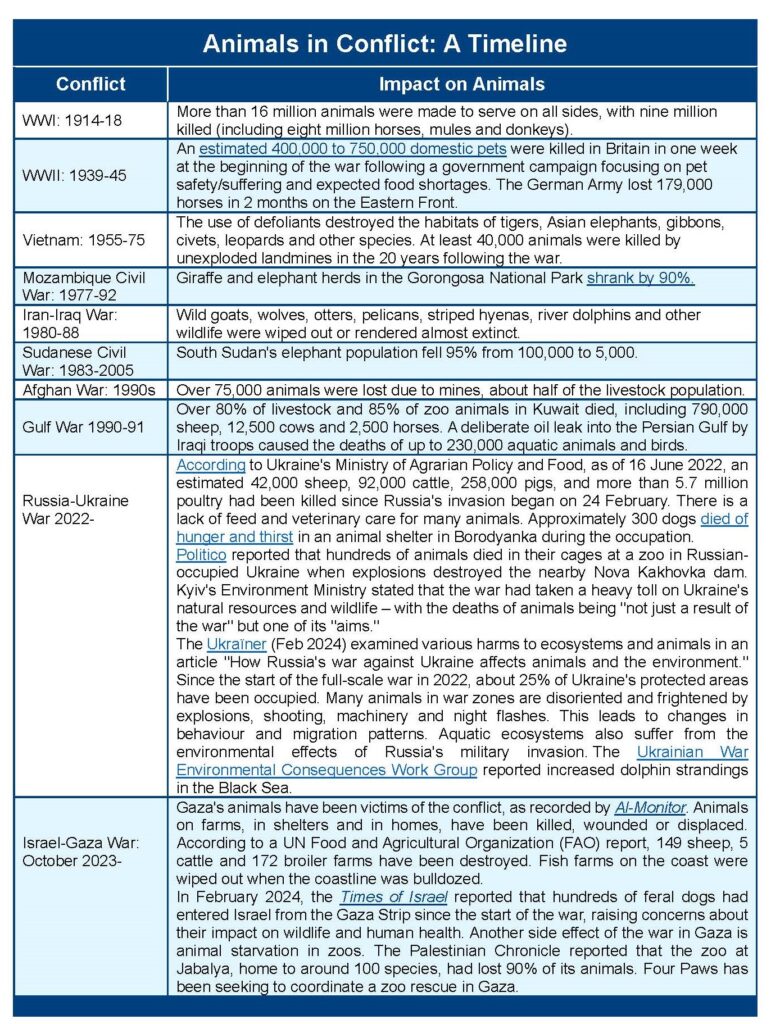

Animals in Conflict: Timeline

Animal Victims of War

What follows briefly examines how conflict can affect wildlife, including marine animals, farmed animals, working animals and companion animals.

Wildlife

Even low-level human conflict can drive dramatic wildlife declines. A study published in the journal Nature analysed data from 1946 to identify the effects of human conflict on large mammal populations in Africa. The results suggested that of all the factors studied, repeated armed conflict had the most significant impact on wildlife – and even low-level conflict could cause profound declines in large herbivore populations. Weakened environmental governance is a critical factor in wildlife loss.

Wild animals can be killed and injured by landmines, while the increased availability of small arms can intensify unsustainable hunting. Wild animals are also hunted and killed for food, both as a coping strategy and for products to be sold to raise funds for the conflict. The extent to which non-state armed groups have used wildlife crime to raise funds is contested. Where the trade and consumption of wild meat (bush meat) started during conflicts, it often continues into peacetime. It has links to One Health (including epidemics/pandemics), biodiversity loss and wildlife trade.

In the oceans, marine animals can suffer through naval exercises and warfare, with common pathologies being decompression sickness and acoustic traumas, possibly exacerbating mass strandings of whales.

Zoos

Zoo animals are often the victims of conflict. In times of war, zoos lack paying visitors, and zoo animals are seen as a liability. The animals may be killed, eaten, injured, starved, stolen, traded, abused, even abandoned or released into the conflict zones as a diversion to distract combatants and slow recovery efforts. Following the invasion of Iraq in 2003, large carnivores, including lions, panthers and jaguars, were released from the Baghdad Zoo and private residences by the retreating Iraqi forces to impede coalition forces from advancing on the city; these animals were either killed or captured and returned to the zoo in the weeks after the onset of conflict.

Livestock

Livestock have been injured in war and specifically targeted and killed. The circumstances often mean that people cannot care for or feed their animals properly, and the animals can succumb to disease. In the chaos of conflict, animals are commonly overworked or eaten, while shortages of veterinary care and veterinary medicines are common.

Working animals

Working animals are essential for transporting people, water, supplies and firewood. However, despite this, they are often slaughtered when food reserves run out or are sold because cash assets are needed, and proper care and feed provisioning are difficult. This leads to further pressures and vulnerabilities for people, especially refugees and displaced persons.

Companion animals

Companion animals can also be victims of war, being killed, maimed, abandoned and sometimes eaten. In times of extreme food shortages, companion animals have been euthanised because owners could not care for them or even eaten by their owners or other people in the community. In many cases, companion animals are abandoned and become lost in the chaos of war, especially when their owners are displaced or become refugees. Displacement of people may fuel a free-roaming (stray) population of former pets, raising public health concerns (e.g., rabies) that may lead to substandard and inhumane population management methods, such as culling with poisons.

Authors:

Janice Cox is a co-founder of World Animal Net, which has since merged with the World Federation for Animals (WFA). She has over 35 years of experience in international animal welfare, focusing on the connections between animal welfare, environmental issues, and development. Based in South Africa, she serves as the Animal Welfare Expert for Southern Africa at the African Platform for Animal Welfare (APAW). She has recently become a member of WellBeing International’s Global Ambassador.

Jackson Zee has over 25 years of experience in emergency management and humanitarian affairs, working in sustainable development, animal welfare and conservation. He is currently Director of Disaster Relief for FOUR PAWS International and is based in Austria.