Aug 29, 2024 Recovering Wild Tiger Population in Thailand

The tiger, a creature of almost mystical, magical, and majestic allure and the subject of Blake’s famous 1794 poem Tyger, is battling for survival in its final refuges in Thailand and Myanmar in Southeast Asia. The populations of tigers in the neighboring countries of Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam have essentially been eliminated. The Indochinese tiger (Panthera tigris corbetti), a subspecies found in Southeast Asia, is approximately 20% smaller with darker, shorter fur, narrower stripes, and a smaller skull than the Bengal tiger found in South Asia (India, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Bhutan). These unique features make the Indochinese tiger a distinct and valuable part of Thailand’s natural heritage.

The tiger, a creature of almost mystical, magical, and majestic allure and the subject of Blake’s famous 1794 poem Tyger, is battling for survival in its final refuges in Thailand and Myanmar in Southeast Asia. The populations of tigers in the neighboring countries of Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam have essentially been eliminated. The Indochinese tiger (Panthera tigris corbetti), a subspecies found in Southeast Asia, is approximately 20% smaller with darker, shorter fur, narrower stripes, and a smaller skull than the Bengal tiger found in South Asia (India, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Bhutan). These unique features make the Indochinese tiger a distinct and valuable part of Thailand’s natural heritage.

Tigers in Southeastern Asia Are in Crisis

The wild tiger populations in Southeast Asia have declined dramatically in the last hundred years due to habitat loss, declining prey numbers, and poaching for the illegal wildlife trade. This trade is driven by the demand for tiger body parts such as skins, bones, paws, and other body parts in China and Vietnam. The substantial number of tigers in captivity in Thailand also fuels the illegal wildlife trade by providing body parts when these tigers age and die.

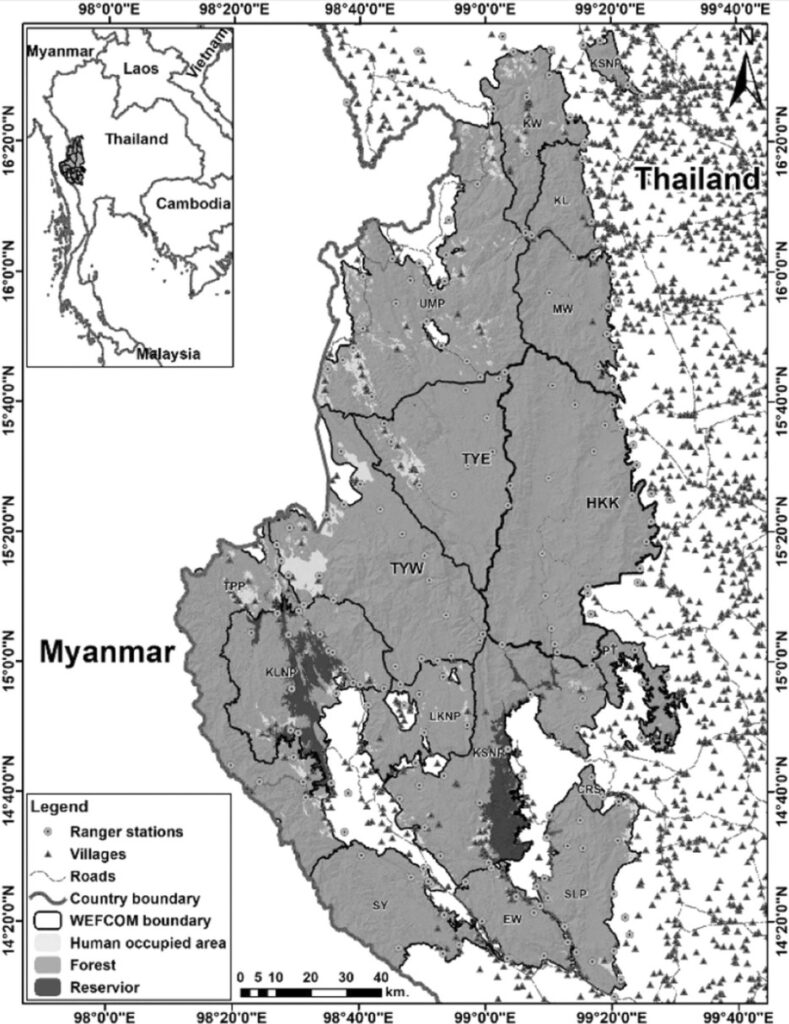

Currently, the largest number of wild tigers in Thailand are found in a large, protected area called the Western Forest Complex (WEFCOM) including connected national parks and wildlife sanctuaries. The Thai government began to establish this integrated ecosystem in 1965. It now includes 12 national parks and 7 wildlife sanctuaries covering 18,730 square kilometers (7,232 square miles – a little smaller than the area of Wales in the UK) that protect a diverse and connected biodiversity ecosystem. Part of the WEFCOM has been declared a UNESCO World Heritage site, including primarily three contiguous protected areas – the Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary (HKK) and the Thung Yai Naresuan Wildlife Sanctuary East (TYE) and West (TYW). HKK is the largest reserve in the WEFCOM at 2,780 km2 (1,074 square miles) and is also home to the largest number of wild tigers. The Thung Yai Wildlife Sanctuary East (TYE ) covers about 1,572 square kilometers (607 square miles), while The Thung Yai Wildlife Sanctuary West (TYW) covers 2,118 square kilometers or 818 square miles.

The Challenge of Counting Tigers

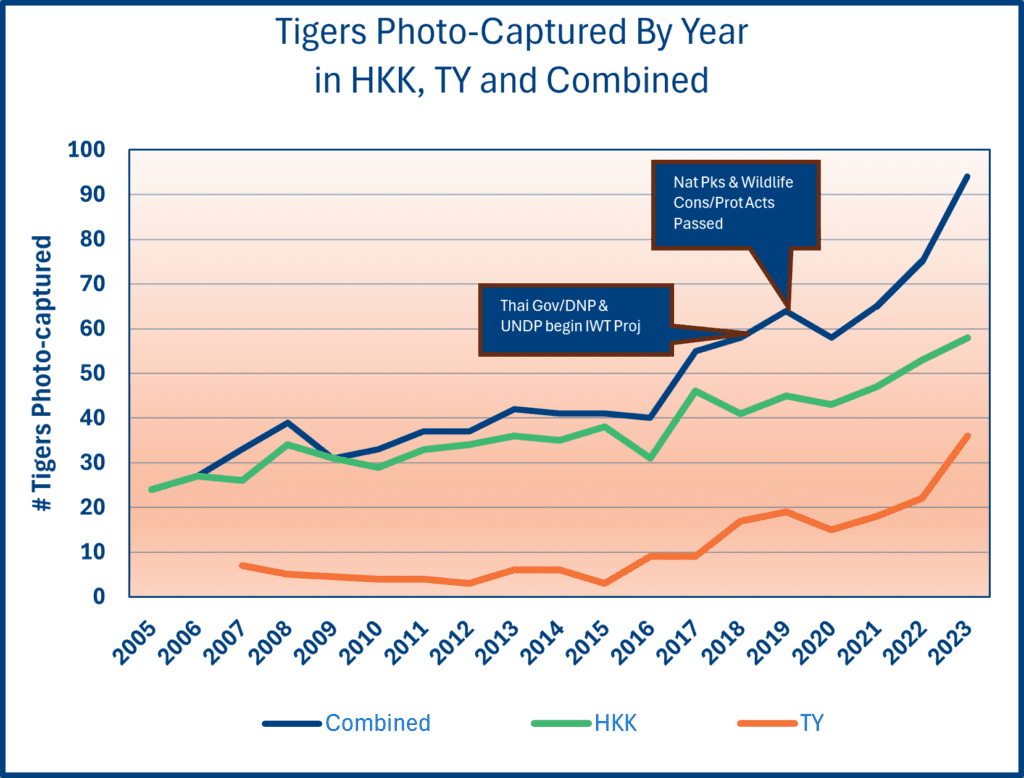

Accurately tracking wild tigers is a challenge. A multinational team from Thailand and India used camera “traps” spread across the HKK and TY protected areas to develop an estimate of the population size of wild tigers by “capturing” (i.e., photographing) individuals and then “recapturing” (photographing) them at a later time. This technique permitted the identification of each tiger by relying on the unique markings and features of each animal observed in the photographs. The camera trapping study in the HKK and TY-protected areas continued for 19 years. The authors reported that the tiger population in the HKK protected area increased from 1.3 to 2.9 tigers per 100 square kilometers over that period and increased in the Thung Yai protected area. Figure 1 illustrates the increases in both protected areas from 2005 to 2023.

Progress is being made in Thailand due to Collaborative Conservation Efforts

Figure 1: Number of individual tigers caught annually on camera traps in the study areas of the Huai Kai Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary and the Thung Yai Wildlife Sanctuary in the Western Forest Complex in Thailand. Data obtained from Duangchantrasiri et al, 2024.

In May 2024, the Thai government announced that wild tiger number estimates had increased in Thailand. They reported that the total wild tiger population had increased from 148-189 individual tigers in 2022 to 179-223 in 2023.

The recovery of wild tigers in Thailand has been a collaborative effort involving multiple organizations and funders. It is led by the Thai Government, the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation along with other governmental support, contributions by the Wildlife Conservation Society, numerous local and international NGOs, and, of course, the people of Thailand.

The Thai government established a network of protective areas and national parks that provided habitats for wildlife. It also invested in developing an effective ranger workforce that patrolled the national parks and sanctuaries and discouraged poaching.

The government institutionalized a Spatial Monitoring and Reporting Tool (SMART) to enhance conservation efforts. Tiger prey populations, particularly sambar deer and banteng, were monitored and restored to support the recovery of endangered carnivores, particularly tigers.

Finally, Thailand’s partnership with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), including funding support from the Global Environment Facility (GEF) to combat the illegal wildlife trade, including in tiger parts, was also essential to successfully increasing wild tiger populations.

Video credit: buddhawut, Shutterstock

Map of the Western Forest Complex obtained from: Duangchantrasiri, S., Sornsa, M., Jathanna, D., Jornburom, P., Pattanavibool, A., Simcharoen, S. and Kanistha, P. 2024. Rigorous assessment of a unique tiger recovery in Southeast Asia based on photographic capture-recapture modeling of population dynamics. Global Ecol. & Conservation 53, e03016.