Dec 31, 2021 Back to the Future and a Sustainable World

As we bid goodbye to 2021, the world continues its struggles with Covid-19 and its new variants. It is only natural to focus on the present and tempting to reflect on periods in the past – a concept encapsulated in the “back to the future” title – when life seemed more straightforward and less complicated. Think back to when only three TV channels (if you lived in America) were available, telephones were wired to walls, and memos were typed in triplicate. Research usually required multiple library trips to consult dusty manuscripts, reports, and books. Although our current challenges can seem overwhelming, we need to remind ourselves that we must also focus on creating a sustainable world for the future. How can we invest in technological innovations that help recycle waste and build and maintain a sustainable world while moving away from approaches that focus on economic growth to the detriment of the planet’s future?

ENERGY

New technologies in the energy sector promise a massive shift in how the world generates electricity and how we might satisfy an increasing demand for energy without compromising planetary health further than we have already. The prices of solar and wind technologies (as examined in Levelized Costs of Energy (LCOE) – the cost of constructing and running power plants) have plummeted, as has the price of battery storage. It is now much cheaper to build and run solar and wind power plants. Furthermore, those costs will likely continue to fall rapidly over the next decade. It will be challenging to move away from existing fossil fuel power plants – inertia and procrastination seem to be built into human behavior – but we need to move as quickly as we can away from fossil fuels. Doing so would deliver massive benefits to the planet, emerging economies that will need clean energy, and human health. Fossil fuel power plants produce carbon dioxide and other pollutants that cause an estimated several million human deaths annually.

LAND USE

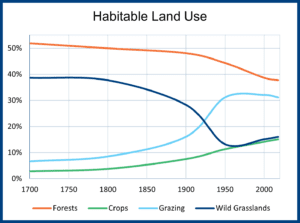

As the world population grows, the size of the human footprint grows as well. Oxford University’s ‘Our World in Data’ center has produced several articles on the changing human footprint over time. The chart below presents some of the data they report using FAO estimates. The loss of wild grasslands and forests (mainly tropical forests) has been substantial since 1900. It is no wonder that grassland species of birds and animals have suffered significant declines. Three-quarters of the recent (since 1950) change in land use is driven by the world’s increased consumption of animal products. A recent paper reports that land-use changes causing wild animal habitat loss may be 3-fold more significant than the FAO reports.

Over three-quarters of land devoted to crops and grazing supports animals raised to produce animal products for human consumption. Intensive animal raising systems are very inefficient. Animal products supply only 18% of total human calories consumed (and less than 40% of protein). In 1961, global per capita meat consumption was around half of today. Switching the food supply “back to the future” when the world ate far less meat would free up land to be restored to its wild state without affecting either calorie or protein availability for humans. It would also reduce pollution from intensive animal systems, including antibiotic residues (perhaps three-quarters of all antibiotics produced in the USA are fed to farm animals), thus improving overall livability in rural communities.

POPULATION

Human population growth has been a controversial issue since 1798 when economist and cleric Thomas Malthus published his book on the subject, including the sentence – “The power of population is indefinitely greater than the power in the earth to produce subsistence for man.” However, Malthus’ gloomy predictions (leading to the characterization of economics as the “dismal science”) were periodically overturned by the opening up of new lands, by industrialization, and by agricultural improvements, until a new generation of environmentalists (e.g., the Ehrlichs and The Population Bomb) reignited the issue in the late 1960s. But, the green revolution in the 1970s again pushed back the projected widespread starvation (the proportion of undernourished people in developing countries declined from 30% in 1970 to 12.9% in 2015. But the proportion of severely food insecure people in the world has been creeping up since 2015. It would thus behoove the world to pay serious attention to population trends and the challenges of providing for substantially larger human populations. The UN Population Division provides three estimates of the future human population. Their low estimate predicts the world population will peak at a little over 8.9 billion in 2054. Their medium estimate projects world population continuing to grow beyond 2100 when there would be 10.9 billion people on the planet. The high estimate (15.6 billion people by 2100) is unlikely and unthinkable if there is any hope of delivering decent living standards and sustainable environments to everybody by 2100.

CONSUMPTION

The low population variant is the one the world should aim for to maximize the chances for maintaining planetary health and human flourishing. Nevertheless, countries below a replacement fertility rate of 2.1 children per woman (India recently reached that number) worry about the impact on their economies as their population begins to fall. Economic growth is still a primary focus for most countries, and a growing domestic consumer base is one way to deliver such growth. Economic growth is still the gold standard (pun intended) for countries (global GDP has increased 5-fold from 1985 to 2020). Efforts to address problems caused by economic growth (climate change is the world’s current focus) typically falter whenever proposals threaten to slow economic growth. With its new Well-being Budget approach, even New Zealand projects annual GDP growth of 2.9%. The world is not yet ready to grapple meaningfully with the idea that we live on a planet that has finite resources. We could better convert solar energy into usable electricity, produce freshwater, and grow food to satisfy basic human needs. We need to address other finite resources and develop better waste management and disposal approaches.

CONCLUSION

We should address energy requirements with new and less polluting technological fixes in the future. Furthermore, we need more intensive efforts to manage population growth, increasing consumption, and the resulting wastes. Although our current challenges can seem overwhelming, we need to remind ourselves that we must also focus on leaving a habitable planet for those beings who share our world.