Nov 29, 2021 Global Dog Campaign Case Studies: Kabul, Afghanistan; Chennai, India; Heredia, Costa Rica

Kabul, Afghanistan

Afghanistan recently experienced a change in government, leading to chaotic scenes at Kabul airport as countries evacuated their personnel and individual Afghan citizens sought to leave the country. Dogs were also caught up in this chaos as some animal advocates sought, mostly unsuccessfully, to evacuate rescued dogs from the country. Mayhew Afghanistan has probably had the best relationship with the Afghan authorities of various animal groups working in the country. In 2017, they persuaded the Kabul municipal authorities to stop culling street dogs (they had been culling approximately 15-20,000 dogs a year) and launch a rabies vaccination drive instead. [Note: the culling of about half the street dogs annually had no apparent impact on the overall street dog population.]

The Mayhew conducted surveys to determine how many dogs lived on the streets of Kabul and to identify how many vaccine doses would be required to vaccinate at least 70% of the street dogs. As a result, we now have a reasonably good estimate of the street dog population (around 30,000), and there may be a further 10,000 owned dogs. As of September 2021, the Mayhew Afghanistan team had administered almost 80,000 vaccine doses and sterilized 21,000 dogs. The number of recorded dog bites in the city had fallen by over fifty percent, and human rabies cases were close to zero (and much lower than during the dog culling period).

The Mayhew Afghanistan team was also able to visit the airport and rescue some of the dogs left there during the chaotic days at the end of August. Mayhew Afghanistan has now been authorized (on September 12) by the new authorities to restart their vaccination and sterilization program. In October 2021, the Mayhew Afghanistan team had sterilized around 600 dogs. We would argue that a big part of Mayhew Afghanistan’s ability to continue their vaccination and sterilization program under the new authorities has been their careful documentation of what has been accomplished and the related impact for both dogs and people.

Chennai, India

India is a challenging country for homeless dogs because most people have a high tolerance for roaming street dogs (of whom there are large numbers compared to homed dogs) and solid cultural beliefs regarding the need to protect animals. On the other hand, India is a low-income country with only limited resources to address animal well-being. Nonetheless, India established rules outlawing dog culls as a means of control in 2001, and sterilization as a humane management approach was further endorsed by the Supreme Court of India in 2015 (and the culling of dogs was determined to be illegal).

India is a challenging country for homeless dogs because most people have a high tolerance for roaming street dogs (of whom there are large numbers compared to homed dogs) and solid cultural beliefs regarding the need to protect animals. On the other hand, India is a low-income country with only limited resources to address animal well-being. Nonetheless, India established rules outlawing dog culls as a means of control in 2001, and sterilization as a humane management approach was further endorsed by the Supreme Court of India in 2015 (and the culling of dogs was determined to be illegal).

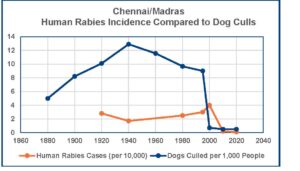

In 1964, Dr. S Chinny Krishna proposed sterilization and vaccination of street dogs as a possible solution for humane dog management. Still, it took thirty years before his proposal began to be put into practice. When sterilization was finally adopted city-wide in the late 1990s, the culling of street dogs was stopped, and the incidence of human rabies cases rapidly fell to zero (see chart). Implementation of street dog sterilization campaigns (all the sterilized dogs were vaccinated against rabies) in other Indian cities led to a drop in human rabies cases. However, the percentage of vaccinated street dogs was not high enough to account for the sudden fall in human rabies cases).

Heredia, Costa Rica

When Lilian Schnog took over a run-down shelter in San Rafael in 1991, many dogs could be observed roaming the streets of Heredia, the local, provincial capital. Roaming dogs were still widespread a decade later. However, by 2015, it was unusual to see a dog roaming the streets of Heredia. This observation raised the question – what had happened to reduce the street dog population? Could the shelter’s presence have had an effect in lowering roaming dog numbers? Could there be a significant change in the human-dog interaction in the country?

Something similar took place in the United States but about forty years earlier. In 1950, the first survey of US dog populations reported around 32.6 million dogs in the country, but that 10 million (30%) were strays (i.e., street/homeless dogs). Thirty years later, approximately 9% of US dogs could be categorized as strays, and today less than 2% are strays.

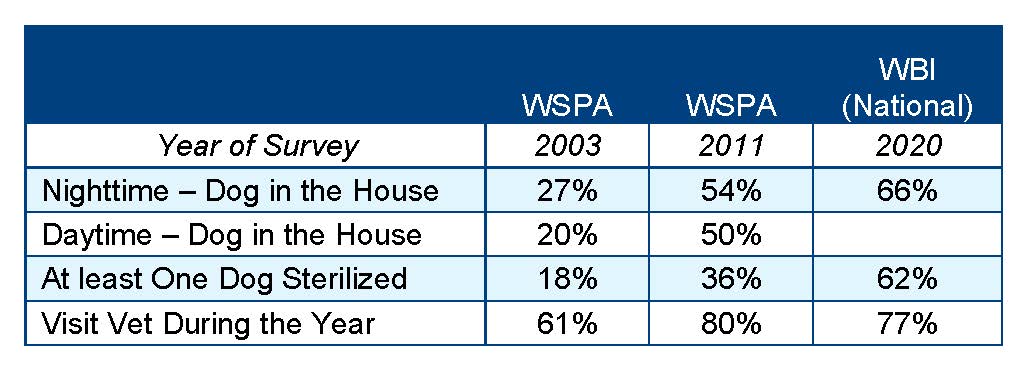

Fortunately, we do not need to guess about the human-dog relationship in Costa Rica. In 2003 and 2011, the World Animal Protection office in Costa Rica (then WSPA) conducted two surveys of the human-dog relationship in the Central Valley (where half the human population in the country lives). Then, in 2020, WBI conducted a survey using some of the same questions countrywide. At last, WBI had comparable time-series on the human-dog relationship in a country. The key results are shown in the table.

Fortunately, we do not need to guess about the human-dog relationship in Costa Rica. In 2003 and 2011, the World Animal Protection office in Costa Rica (then WSPA) conducted two surveys of the human-dog relationship in the Central Valley (where half the human population in the country lives). Then, in 2020, WBI conducted a survey using some of the same questions countrywide. At last, WBI had comparable time-series on the human-dog relationship in a country. The key results are shown in the table.

The human-dog relationship in Costa Rica has changed substantially in the last eighteen years. The dogs are now being kept in the house or yard rather than roam the streets. Also, the proportion of dog-owning households with at least one dog sterilized has jumped from 18% to 62% from 2003 to 2020. This change is dramatic, and WBI suspects that other countries in Latin America may be going through a similar transition.

Conclusion

The above are just a handful of examples of humane dog management projects currently being implemented worldwide. Other successful projects are being undertaken in countries (e.g., Bhutan and Thailand), states (Sikkim and Uttarakhand in India), and cities (e.g., Negombo, Sri Lanka, and Oradea, Romania) around the world. Small animal veterinary clinics are springing up across Asia and Latin America. Due to these and other implementers’ successful efforts along with the data infrastructure, analyses, reporting, technical and direct project support provided by the GDC to augment their efforts, WBI is very bullish on the prospects of eliminating dog homelessness in the coming decades.